Nenets activities. "Nenets and their traditions." Materials and tasks for work on the implementation of the national component. Number of Nenets in Russia

Like other Northern Samoyedic peoples, the Nenets were formed from several ethnic components. During the first millennium AD. Under the Huns, Turks and other warlike nomads, the Samoyed-speaking ancestors of the Nenets moved to the north.

Previously, they inhabited the forest-steppe regions of the Irtysh and Tobol region, and after the resettlement they occupied the taiga and the Arctic and Subpolar regions and assimilated the aboriginal population - wild deer hunters and sea hunters. Later, the Nenets also included Ugric and Entets groups.

Among the Nenets, tundra and forest Nenets are distinguished. They differ in dialects and some ethnocultural features. Forest Nenets lived in the Purovsky and Nadymsky districts of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, in the Surgut and Beloyarsky districts of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug. Settlement over such a large territory was due to the variety of contacts of the Nenets with other peoples: Russians, Komi-Zyryans,. Related peoples are the Nganasans, Enets, and Selkups. Currently, the Nenets inhabit vast territories autonomous okrugs Nenets, Yamalo-Nenets, Khanty-Mansiysk.

The Nenets speak the Nenets language of the Samoyed group of the Ural family, which is divided into (it is spoken by most Nenets) and forest dialects. Today, the Russian language is widespread among the Nenets; writing was created in 1936 on the basis of Russian graphics. The Nenets of the south of the Bolshezemelskaya tundra speak the Izhem dialect of the Komi language.

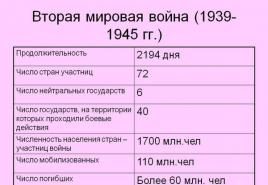

According to the 2002 population census, in the territory Russian Federation More than 41 thousand Nenets lived.

The traditional occupations of the Nenets are nomadic reindeer herding, hunting fur-bearing animals, wild deer, upland and waterfowl, and fishing. From the middle of the 18th century. The leading branch of the economy was domestic reindeer husbandry with year-round grazing of deer under the protection of shepherds and dogs.

The Nenets led a nomadic lifestyle, making large migrations, moving with herds to the sea in the spring, and back to the region in the fall. A herd of 70-100 heads provided the farm with everything necessary. Small households spent time near rivers and lakes, fishing. Fishing was especially developed in the lower reaches of the Ob, Nadym, Pura, Taz. The Nenets especially valued sturgeon, whitefish, and salmon species of fish, as well as ide and navaga. Fish were caught with nets and traps.

The Nenets hunted wild deer and fur-bearing animals - arctic fox, fox, hare, ermine. Group hunts were organized for poultry (geese), and they were driven into nets. Firearms appeared among Nenets hunters no earlier than the 18th century. Until the beginning of the twentieth century. a compound (glued) bow 1.5-2 meters long was used. The Nenets, especially the western groups, were also engaged in sea hunting: they caught seals, bearded seals, beluga whales, seals, and walruses. The animal was concealed using a shield on runners; when catching seals, hooks installed on a hole were also used.

Until the end of the 19th century. The main social unit of the Nenets was the patrilocal clan (erkar). The Siberian tundra Nenets have preserved 2 exogamous phratries. Nenets kinship terms date back to the era of group marriage. For a long time Polygamy was maintained, a bride price and ransom were paid for a wife, and there was a custom of blood feud between clans.

The traditional dwelling is a collapsible tent covered with reindeer skins in winter and birch bark in summer. Outerwear (malitsa, sokui) and shoes (pima) were made from reindeer skins. They moved on light wooden sledges. Traditional food is deer meat and fish.

Christianity was introduced in the first quarter of the 19th century. among the Nenets of the Arkhangelsk province. Despite the fact that the Nenets were converted to Orthodoxy, great importance continued to have traditional beliefs. Folk beliefs in spirits - the masters of heaven, earth, fire, rivers, and natural phenomena - were preserved. The wolf was considered the embodiment of the evil principle, whose real name - “sarmak” - could not be pronounced out loud.

Sacrifices were made to Christian saints, for example, Nicholas the Saint, just like idols. Shamanism was very widespread. In 1898, a “foreign boarding school” was established in Obdorsk, but all attempts to educate the Nenets through the Christian Church were unsuccessful. An attempt to create the Nenets alphabet was made in the 1830s. Archimandrite Benjamin, translating the Gospel to him. However, this “alphabet” was not approved by anyone, including the Synod. A new writing system and primer for the Nenets were created in 1932.

This people may be small, but they have succeeded in many ways. Keep your fingers crossed: the Nenets are the largest of the indigenous small ethnic groups in the north of Russia (44,640 people according to the 2010 census, the “bar” for being considered an indigenous indigenous peoples is 50 thousand people). Its representatives have one of the highest levels of proficiency in the national language (more than 70% call Nenets their native language). And this is the only northern ethnic group whose name is mentioned in the names of as many as three administrative-territorial entities: the Nenets and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrugs, as well as the Taimyr Dolgano-Nenets Autonomous Okrug municipal district in the Krasnoyarsk region.

Bloodthirsty customs

The self-name Nenets (nenech) is translated as “man”. This name was assigned to representatives of this ethnic group relatively recently - since 1930. In the old days they were called Samoyeds or Yuracs.

The Church Slavic word "samoyad" means "cannibal". It is believed that the inhabitants of the tundra were nicknamed this way for the ancient custom of cult cannibalism. In ancient orders, the word “raw food eaters” is also found, that is, those who consume raw meat. The first mentions of the Nenets were found in the chronicle of Nestor (1096). Even then they were known to Novgorod traders. Since the 16th century, an intensive movement of industrialists to the east began, and Russian strongholds began to appear in the Nenets territories.

By the way, the Nenets did not always live there. According to the most common modern hypothesis, the homeland of this Samoyed people is Southern Siberia. During the first millennium AD. Most of it, under pressure from other tribes, moved along the Ob and Yenisei into the northern taiga, and then into the tundra, where it assimilated the Arctic population. Later, the ancestors of the Nenets settled in the lands from the Mezen River to the Yenisei.

Oleshek in nannies

The Nenets call themselves children of the deer. This animal gives them not only food and clothing, but also the meaning of existence. It is believed that a herd of up to one hundred heads provides the farm with everything necessary. The Nenets even say: “Deer brings happiness.”

However, asking a Nenets how many heads he has in his herd is considered indecent. Representatives of the people are characterized by modesty and silence, ignoring questions that they do not like. The Nenets have a special inner world that is not always understandable to residents of megacities.

The phrase “children of the deer” also has a direct meaning. A few animals from the herd are usually kept as pets, which are called "awks". They live in the tent and partially serve as nannies for children. In general, all deer are divided according to their purpose: for transporting goods, for racing, for good luck. White deer are considered sacred and are forbidden to be slaughtered for meat. A sign of the sun or images of spirits are carved on their sides, and the horns are decorated with red ribbons.

On the sledge - on the left side

Means of transportation in the tundra all year round sledges serve. These narrow sleighs are made from spruce or birch.

Light sleds have different purposes. Men's only have backrest, female - also front and side for transporting children. Unlike other northern peoples, the Nenets always sit on the sledge on the left side. A light sleigh is usually harnessed to up to six reindeer. Single bulls are considered the fastest and most resilient: they can run up to 300 km in a day. They begin to be accustomed to sledges at the age of six months.

A rein and a trochee, a pole up to 5 meters long with a bone tip, help control the deer. The harness itself is decorated with tassels and bells. Cargo sleds differ from passenger sleds in structure; they are harnessed by two reindeer. Five or six cargo sleds connected to each other are called “argish” (reindeer wagon).

Hunting is worse than bondage

The main occupation of the Nenets, starting from the 18th century, is large-scale reindeer herding. Their whole life is subject to the rhythm of the movement of animals in search of food: in the summer - to the north, in the winter - to the south. Reindeer huskies help move the herd.

The main occupation of the Nenets, starting from the 18th century, is large-scale reindeer herding. Their whole life is subject to the rhythm of the movement of animals in search of food: in the summer - to the north, in the winter - to the south. Reindeer huskies help move the herd.

Traditional activities of the Nenets are also hunting and fishing. Wild staghorn is caught using crossbows, camouflage shields, pursuit on skis, mass slaughter at water crossings, or bait with domestic reindeer. Mouth traps, snares or snares are placed on fur-bearing animals. Of the birds (hog and waterfowl), only the seagull, which is considered sacred, is not hunted. Fish is caught with nets and seines from boats; in winter, they break through the ice and spear the prey with spears.

Plague as a model of the universe

Reindeer herders usually move across the tundra in several families: this makes it easier to monitor the herd. Several traditional dwellings - tents - make up the camp.

Installing a chum is traditionally a woman's job. The choice of location depends on the time of year. In winter, they try to shelter the home from the winds; in summer, they try to place it on ventilated hills. Up to 40 poles are used for its construction. In winter, the tent is covered with reindeer skins (up to 75 animals), and in summer with birch bark.

For the Nenets, their home is a miniature model of the world. The hole at the top symbolizes the connection with the sun and moon, the poles symbolize the airy sphere enveloping the Earth. It is believed that the more spacious the tent, the richer the family. Prosperity can also be determined by the top of the dwelling: among the poor it is pointed.

Know your corner

Inside the home, everything is subject to its own logic. In the center there is a fireplace where food is cooked. There are sleeping places on both sides of it, and dishes and religious objects are placed opposite the entrance.

Inside the home, everything is subject to its own logic. In the center there is a fireplace where food is cooked. There are sleeping places on both sides of it, and dishes and religious objects are placed opposite the entrance.

The only furniture is a small table. The beds are made of deer skins, spread on mats on top of wide boards. Babies are kept in cradles filled with dry moss. Again, deer skins serve as diapers. Inside there are many tools that the men make themselves. Harsh life requires everyone to be a jack of all trades. A woman's job is to chop wood, light a fire, cook food, and look after children.

Dolls for girls are “nuhuko” - beaks of ducks or geese with sewn flaps. Boys love to play with antlers and lasso imaginary deer. From the age of four they are taught to prepare harness and drive sledges.

"Kalotushka" and kopalchen

The basis of the Nenets diet is meat and fish. Due to constant use raw meat and they are not in danger of scurvy. In harsh climates, this is necessary to replenish the natural need for vitamins.

Fresh meat is especially valued. The deer is stunned with a blow from the butt of an ax and then stabbed with a long knife through the ribs so as not to shed a drop of blood. Everyone cuts off a piece of the carcass and dips it in warm blood. Antlers are considered a delicacy - young horns, the cartilage of which is filled with blood vessels. The Nenets love unprocessed kidneys and liver, tongue, heart, and rennet. They also eat kopalchen (rotted meat), blood fritters, and soup with flour. In addition to venison, they prepare beef and pork, meat of sea animals and poultry. In winter, stroganina and “kolotuska” are popular - frozen fish, which is smashed whole on the table. Drinks they prefer are tea, berry compotes and fruit drinks, and jelly.

There are many signs associated with eating. It is forbidden to laugh at food; it is forbidden to finish eating for the elderly. And the fallen piece (a sign that those who have gone to the lower world want to eat) is supposed to be left near the hearth.

Fur to the body

Dressing reindeer skins, sewing clothes and decorating with ornaments is traditionally a woman's job. When “sorting” raw materials, the age of the deer is taken into account, as well as from which part of the body the skin was removed. The skin of a calf aged three months, taken at the end of summer, is especially valuable.

Dressing reindeer skins, sewing clothes and decorating with ornaments is traditionally a woman's job. When “sorting” raw materials, the age of the deer is taken into account, as well as from which part of the body the skin was removed. The skin of a calf aged three months, taken at the end of summer, is especially valuable.

Men's clothing is a malitsa with a hood, worn on a naked body with the fur inside. An indispensable attribute is a leather belt from which a knife, a bag of flint and a bear fang are hung for good luck on the hunt. Men's shoes - pima - fur boots.

Women wear a fur coat called a gentleman. The top is made from kamus (skins from the upper part of the legs of a deer) with the fur facing out, the bottom is made from arctic fox. Pans are decorated with fur mosaics, tassels and piping. A cloth cover with an ornament is put on top. They are belted with a long belt with a copper ring-buckle. The fur bonnet – sava – is worn separately.

Az and beeches of the Nenets

The Nenets speak the language of the Samoyed group, which, together with the languages of the Finno-Ugric group, forms the Uralic language family. There are two dialects - tundra and forest.

The first Nenets primer “New Word” based on Latin graphics was prepared by G.N. Prokofiev in 1932. Subsequently, grammar reference books, textbooks and books for reading in the Nenets language were developed. In 1936, the writing of the ethnic group was transferred to a Cyrillic graphic basis. Nowadays, educational and fiction, periodicals, radio broadcasts.

Ekaterina Kurzeneva

The self-name of the majority of the tundra Nenets (for the division of the Nenets into tundra and forest, see below) - ?enej ?ene??, from where Russian Nenets, Nenets, literally means " real man”, and similarly to the self-names of the Enets and Nganasans formed from the same Northern Samoyedic roots (see below). The eastern tundra (the mouth of the Ob and to the east) Nenets also use the word ??sawa"man". Forest Nenets call themselves (plural) ?ak?(by genus name ?ak, possibly related to Nen. ?a“tree, forest”), and the tundra Nenets call them ?an ??sawa?"forest people"

The external name of the Nenets, which serves in European languages and today also as the name of all Samoyeds, is German. (plural) Samojeden etc. - comes from Russian Samoyeds, which until the 1930s served as the name of the Nenets, as well as - with clarifying definitions - other Samoyeds (see). Old Russian Samoyed appears for the first time already in the initial Russian chronicle under 1096 in the story of the Novgorodian Gyuryata Rogovich, as the name of the people living further to the north (and east -?) from Ugra(see sections on Mansi and Khanty, see also below). Form Samoyed coincides with the church glory. selfish"cannibals". The use of the word “cannibal” to name the population of remote and poorly known regions in ancient Russian monuments may be due to the medieval literary tradition (going back to the “Roman of Alexander”) of stories about mythical peoples inhabiting the outskirts of the ecumene (such as “dog heads”, “mouthless”, etc. . P.). It is in this context that they first meet Samoyeds(in the shape of Samogedi) in Western European sources - in the writings of the papal ambassador to the court of the Mongol Khan br. Joanna de Plano Carpini (mid-13th century): between steam-feeding mouthless parossites And dog heads. It is important that information about these peoples br. John apparently received it from a Russian informant or translator (cf., for example, the name “mouthless”: Parossity- apparently distorted (other?)Russian. ferry-full(version by A. N. Anfertyev), as well as Samogedi- from Russian Samoyeds). Perhaps the correlation of the mythical “cannibals” ( Samoyeds) the outskirts of the ecumene with the real ancestors of the Nenets contributed to the military customs that existed among peoples in the Middle Ages Western Siberia and, in particular, among the Nenets, associated with dismembering the body of a killed enemy and eating his heart or brain, in connection with which the Pelym Mansi (according to the dictionary of B. Munkacsi) called the Nenets kh?l?s-t?p ?r?nt"cannibals", lit. "Nenets human food." Perhaps it was the stories of the Mansi or their other neighbors (Komi, Ugra) about the military customs of the Nenets and served as the basis for the application of church glory to them by the Russians. words selfish.

There is a widespread version in literature (since the time of M. A. Castren), according to which the word Samoyed(Old Russian) selfish) comes from a certain derivative of the common Sami * s?m?-??ne?m"Sami land". From a historical point of view, such a hypothesis has a right to exist: according to Russian sources and toponymy, in the Middle Ages the Sami or a population close to them in language actually lived in the modern Russian North - almost to the western border of today’s Komi Republic in the east (see section on the Sami) and hence the type name * s?m?-??ne?m, as all the Sami today call their lands, could indeed be used in relation to the territories of the north-east of Eastern Europe, could be known to the Russians and subsequently be transferred to the inhabitants of the extreme North-East - the Nenets. Phonetically, however, Old Russian. Samoyed hardly deducible from * s?m?-??ne?m. The assumption is about the (para?) Sami proto-form of the Russian word like * s?m?-(j)???ne?(m) is also unlikely, since in those Sami dialects where the development of *? n? > *??n?, a similar development is taking place *? m? > ??m?(we are talking here about southern dialects: cf. Sami. (Umeå) sabmee"Sami" e?dnama"earth", (Luleå) sapm?"Sami" ?tnam"earth" - at (Inari) s??mi"Sami" ??nnam"Earth").

The assumption of a connection between Old Russian and Russian is even less reliable. Samoyed with the name of the Tundra Enets somatu(see etymology in the section on Enets) - both for phonetic and historical-geographical reasons. Possible existence of ethnicons in the northeast of Eastern Europe and the north of Western Siberia * s?m?-??ne?m And somatu contributed transferring to the native population the church glory consonant with them. selfish"cannibals", but bring out the old Russian name Nenets cannot be one of these ethnic groups.

Eastern (from the Yamal peninsula and east) Nenets appear in Russian documents of the 17th-19th centuries also under the name yuraki, where their (and often the Nenets in general) Western European names like German come from. Jurak-Samojeden. Rus. yuraki does it contain a suffix? ak, and its basis is a borrowing from the Ob-Ugric (most likely Khanty) languages: mans. (WITH) j??r?n"Nenets", (Sing.) ?r?n, (Con.) j?r??n / jor??n"tzh", hunt. (WITH) j?rn??“Nenets, Nenets” (Wah) j?r?an?, (You.) j?rk?an?, (YU) j?r?n"tzh". The Komi name Nenets was borrowed from the Ob-Ugric languages. jaran. The further etymology of this word remains obscure. What is noteworthy, however, is the closeness of the reconstructed Mansi proto-form * jo?ren(in this case, one should assume metathesis in the Kondinsky dialect of Mansi and the borrowing of a form like Mansi. (Kond.) jor??n into Khanty - otherwise it would be difficult to explain the reduced vowel in the Khanty word with a long one in most Mansi dialects) to the Komi name of the Ob Ugrians * je?gra (< общеперм. *j?gra, see sections on Mansi and Khanty). It is possible, therefore, that the Ob-Ugric name of the Nenets comes from the name of the ancient population of the extreme north-east of Europe and the north of Western Siberia - the chronicle Ugra.

Besides Samoyeds And Ugra in Russian sources of the 11th-15th centuries it is mentioned in the northeast Pechera(in the story of Gyuryata Rogovich of 1096 they are placed in the following order - apparently from (south?) west to (north?) east - Pechera, Ugra, Samoyed). The ethnicity of this group remains unclear. Regarding the etymology of the word Pechera There are two worthy hypotheses. According to the first of them (M. Vasmer), it comes from the name of the river Pechory(Old Russian) Pechera), which, in turn, is purely Russian in origin and is associated with other Russian. oven“cave” - there are really a lot of caves in the lower reaches of the Pechora. According to the second version (L.V. Khomich), the primary name is the name of a certain people oven, after which the river is named, and which comes from the Nenets p?-t?er"mountain dwellers" (nen. p?- lit. “stone”, used in the names of the Ural Mountains, the mountain range on the Kanin Peninsula, the Black River in the Bolshezemelskaya tundra, etc.). Nen. p?-t?er was indeed used as the name of the Nenets groups living on the Siberian side of the Polar Urals and in the Lower Ob region (hence the name of the Nenets of the Polar Urals in Russian sources " stone samoyeds", from the 15th century - as opposed to " to the grassroots Samoyeds", who lived in the tundra of the right bank of the Lower Ob and to the east). If the second of these hypotheses is correct, then under the chronicle Pecheroy Some group of Nenets may be hiding, inhabiting the foothills of the Urals or the spurs of the Timan Ridge, and the presence of Nenets in the Pechora basin already in the 11th century is indicated by the Nenets origin of the name of the people who lived here. If this assumption is incorrect, then the presence in Russian monuments of the 11th-15th centuries in the extreme northeast of Europe of two peoples of unknown ethno-linguistic affiliation - Pechery And Ugra- leaves little room for the Nenets, and the confidence of some researchers regarding localization Samoyeds XI century (who lived, according to unambiguous data from Russian sources, behindPecheroy And Yugra , that is, further to the east and / or north) west of the Urals and, therefore, the conclusion about the penetration of the ancestors of the Nenets into the north of Eastern Europe already at the very beginning of the 2nd millennium AD. e. turn out to be quite controversial.

The first contacts of the Nenets with the Russians in the XI-XIV centuries are replaced by their gradual subordination to the power of the latter - especially from the XV century, when Novgorod lands, including the North, came under the control of Moscow. In 1499, Pustozersk was founded in the lower reaches of the Pechora (next to the modern city of Naryan-Mar) - a stronghold Russian state in the extreme northeast of Europe. Documents from the 16th century are already called Kaninsky, Timansky, Pustozersky Samoyeds- apparently, one should speak with confidence about the Nenets presence in the tundra and forest-tundra of Eastern Europe from the Urals to the Kanin Peninsula only from this time.

At the end of the 16th century, in addition to Pustozersk, where up to two thousand Nenets gathered in winter to trade and pay yasak, Russians founded new settlements in the European North: Mezen on the river of the same name, Ust-Tsilma and Izhma in the middle reaches of the Pechora, to which they were assigned to pay yasak. most European Nenets. During the 17th century, there was an increasing influx of Russians and (in the Pechora basin, primarily Ust-Tsilma) Komi to the northern lands, which, along with the tightening of yasak taxation, led to conflicts with the Nenets, who in the winter of 1662/1663. Pustozersk was burned.

The military activity of the Nenets, however, increased in the 17th century not only in northeastern Europe, but also in Western Siberia; Apparently, it was during this period that the Nenets “took revenge” in wars with the Ob Ugrians who had earlier advanced to the lower reaches of the Ob (the tundra Nenets formed clans that traced their origins to the Khanty) and began their expansion in the tundra zone to the east, to the lands of the Enets (see below). This circumstance is explained, in addition to the increasing pressure on the Nenets from the west, by an important shift in the system of economic life of the tundra Nenets.

Apparently, until about the 16th-17th centuries, their economic structure was basically similar to that of other northern Samoyeds, Enets and Nganasans that persisted until the 20th century, that is, the basis of the economy was fishing and hunting, especially hunting for wild reindeer with using its seasonal migrations. Reindeer husbandry should have been known to the ancestors of the Nenets since the general Samoyedic era, as evidenced by the reconstructed vocabulary of the Samoyedic proto-language, but until the 16th century it had purely transport and auxiliary (reindeer decoys, etc.) significance; people’s lives did not depend on numbers and movements domestic flock. In the 16th-17th centuries, as a result of Russian colonization, the increasing flow of Russian and Komi immigrants, the spread of firearms, the development of market relations and the growth of yasak taxation, there was a sharp intensification of traditional hunting, which quickly led to a reduction in the number of wild reindeer. Traditional methods round-up and driven hunting become unproductive in the north of Eastern Europe, in the Polar Urals, and somewhat later in the north of Western Siberia and decline. On the other hand, due to the need to pay tribute and the development of the fur trade, fur fishing is developing, associated with the need to catch large areas, which has increased the role of transport reindeer husbandry.

Under these conditions, the Nenets of the European and Ural-Ob tundras switched in the 16th-17th centuries to large-herd reindeer husbandry and related nomadic image life (this hypothesis is best substantiated in the works of A.V. Golovnev). The sharp increase in the herd population of reindeer associated with this (for normal reproduction of the herd and maintaining the economic minimum of one farm, 400 or more heads of reindeer were required - for comparison, I will point out that the herds of European Nenets in the 16th century, according to Russian documents, did not exceed 100 heads), led to an active search for new pastures, and high mobility and relative independence from natural conditions ensured the clear superiority of the tundra Nenets over other peoples who preserved a more archaic way of life.

The initial impulse of the Nenets movement in the tundra was directed to the east - from the Polar Urals and the lower reaches of the Ob to Gydan, to the Taz and further to the Yenisei. Even at the beginning of the 17th century, there were apparently no Nenets on Gydan and in the lower reaches of the Taz; these territories were inhabited by “ Hantaic», « Tazovsky», « Khudoseysky» Samoyeds, who paid yasak in Mangazeya (see below), in whom researchers see the ancestors of the Enets (B. O. Dolgikh, V. I. Vasiliev). Nenets (“ stone" And " Obdorsky» Samoyeds) paid yasak in Obdorsk at that time (see below), their appearance as yasak payers in the lower reaches of the Taz and to the east begins to be recorded in the 30s of the 17th century. It is in connection with the movement of the Nenets to the east that the term begins to be often used in Russian documents yuraki(see above). In the 18th century, in the extreme east of the Nenets territory, on the left bank of the Lower Yenisei, G. F. Miller recorded a special dialect of the Nenets language, called “ yuratsky”(now disappeared), which in a number of features was a dialect transitional from the tundra Nenets to the Entets language (according to E. A. Khelimsky). Perhaps it was the last remnant of the chain of transitional dialects that existed before the Nenets expansion, connecting the Northern Samoyedic languages. However, in the lower reaches of the Taz and on Gydan, there was also a simple inclusion of the Entsy and entire Entsy groups into the Nenets clans (at the same time, the descendants of these Entsy, until recently, called themselves Nenets, and the rest of the Nenets - yurakami).

Gradually, during the 17th-18th centuries, the Nenets pushed the Enets back to the Yenisei. The decisive clash occurred (according to V. I. Vasiliev’s reconstruction) in the winter of 1849/1850. on Lake Turuchedo, located in the lower reaches of the Yenisei on the right bank of the river. Judging by the legends, in addition to themselves, the Nganasans and Tungus (Evenks) took part in the battle on the side of the Enets. Enets and Nenets legends differ in their assessment of the outcome of the battle; it is only clear that after it, a border was established between the Enets and Nenets lands along the Yenisei, which remains to this day. However, this did not prevent the Nenets from subsequently making military expeditions to the east, to the Nganasan and Ket lands.

The development of the tundra by nomadic Nenets reindeer herders was directed not only to the east, they penetrated into the northern tundras of Yamal, Gydan, and the Polar Urals; in the 19th century, the tundra Nenets advanced to the islands of Kolguev, Vaygach, and Malaya Zemlya. There they encountered the local population who lived in the Far North, as can be judged from archaeological data, since ancient times. The main occupations of these Arctic natives were river fishing, hunting and sea animal hunting. Some information about the culture of this population - the inhabitants of the coast of the Barents Sea, the Yamal Peninsula and the islands of Vaygach, Malaya Zemlya, etc. - was left by Western European travelers of the 16th-17th centuries: Stephen Barrow, Jan G. van Linschoten, especially Pierre-Martin de Lamartiniere ( mid-17th century). The most interesting in their reports are the descriptions of dugouts with ceilings made of whale bones, comparable to the dwellings of the Koryaks, Itelmens and Eskimos and with the remains of dwellings of the aborigines of the Yamal Peninsula discovered by archaeologists, and frame skin-covered boats such as Eskimo kayaks. In Nenets folklore, the Arctic aborigines are called sikhirtyya(nen. ?i?irt??) and are described as people of short stature, speaking a special language, but also understanding Nenets, living in dugouts, not having deer, with whom the Nenets bartered, sometimes married, sometimes fought. In the end everything sikhirtyya“went underground,” although some Nenets families and clans traced their ancestry back to them. Judging by archaeological finds (primarily the excavations of V.N. Chernetsov on the Yamal Peninsula) and according to Nenets folklore, assimilation sikhirtyya The invasion of the Nenets ended in some areas (in particular, in Yamal) only in the 19th century.

Regarding ethnicity and language sikhirtyya There is no reliable data (except for indications from Nenets folklore about the difference between their language and Nenets). In Russian ethnography (V.N. Chernetsov, V.I. Vasiliev, Yu.B. Simchenko and others) it is customary to see in them the remnant of the ancient population of the Arctic and subarctic zone of Eurasia (or at least Western and Central Siberia), linguistically belonging to the Uralic language family in the broad sense (“para-Uralians”). The participation of Arctic aborigines in the genesis of not only the Nenets, but also the Northern Samoyeds in general is assumed.

In the lower reaches of the Pechora, the Nenets have clashed with the Komi since the end of the 15th century, and Russian documents from the 16th-18th centuries reflect the struggle of the European Nenets for their land on the Pechora. Already in the 17th century, the Lower Pechora (Izhemsk) Komi borrowed domestic reindeer husbandry from the Nenets. In the 19th century, after the suppression of the militant uprisings of the Nenets and in connection with the formation of the capitalist market, the expansion of the Komi-Izhemtsy into the tundra began - first for trade, and then for reindeer herding. Over the course of several decades towards the end of the 19th century, the Komi-Izhemsky reindeer herders established themselves in the Bolshezemelskaya tundra, while their reindeer herding was of a clearly commercial nature and surpassed the Nenets in economic efficiency. This, naturally, led to the fact that the Nenets often ended up as shepherds for the Izhemsky rich reindeer herders, adopted the Komi way of life and language, and arose mixed marriages(the custom of marrying Komi-Izhemok women was widespread even among the Kanin Nenets, thanks to which the Komi language became the language of intra-family communication in the first half of the 20th century).

As a result, in the middle of the 19th century a special ethnographic group formed here Kolva Nenets(after the name of the Kolva River and the village of the same name), who speak a special dialect of the Komi language, but trace their origins to the Nenets, retain mainly Nenets traditional culture and call themselves kolva jaran- “Kolva Nenets” (in the Komi language). Part of the Kolva Nenets in late XIX century, she even switched to a sedentary lifestyle, completely adopting the Komi-Izhem traditions of material culture and economy.

In 1887, four Komi-Izhem families with their herds, fleeing an epizootic, crossed the ice from the Bolshezemelskaya tundra to the Kola Peninsula. Then, in the 90s of the 19th century, other Komi-Izhemtsy joined them. Together with the Komi, their Nenets shepherds also moved to the Kola Peninsula.

The turbulent events of the 17th-19th centuries, which took place in the tundra from the Kanina Peninsula to the Yenisei, almost did not affect only one group of Nenets - Forest Nenets(nen. (L) ?ak?, (T) ?an ??sawa?- see above), living in the Western Siberian taiga of the upper reaches of the Pur, Nadym, Poluy and Kazym rivers, on Lake Num-Tor. Until the 20th century, they retained the old economic way of life, the basis of which was hunting, including wild reindeer, and net and seine (the latter, obviously, after becoming familiar with Russian factory-made nets) fishing. Reindeer husbandry was not a large herd, and therefore, such grazing methods, unthinkable for the tundra Nenets as fumigating the herd with smoke from midges, were possible; seasonal nomads obeyed the rhythm of hunting and fishing life rather than the needs of reindeer herding. In general, the economy of the forest Nenets was, until the 20th century, mainly of a subsistence nature, which led to their significant isolation, secrecy and isolation from external influences, in contrast to their active and mobile tundra fellow tribesmen. Thanks to this, the forest dialect of the Nenets language is significantly different from the tundra language and retains some archaic features.

In Russian documents, the Forest Nenets have been known since the 17th century under the name kunnyh(until the beginning of the 18th century) or Kazym Samoyeds(used until the 20th century). During the 17th-20th centuries, the area of settlement of the Forest Nenets changed slightly (they penetrated into the upper reaches of the Agan River, separate groups may have entered the tundra and moved east to the Taz basin, to the Yenisei). It is unlikely that their number ever exceeded 10% of the total number of Nenets. Currently it is estimated to be about 2 thousand people.

Already from the 16th century, after the conquest of Western Siberia by Ermak (see sections on the Komi, Mansi and Khanty), Russian colonization also covered the lands of the Siberian tundra Nenets. Its stronghold here becomes Obdorsk, founded at the end of the 16th century, to which it is assigned to collect yasak from the tundra Nenets of the Polar Urals, Lower Ob, Yamal, and then the lower reaches of Nadym, Pura, Taz - Obdorsky Samoyeds. Separately, they took into account the Nenets who lived in the basins of the Ob tributaries of the Synya and Lyapin rivers, and assigned to the Voykarsky town, which stood on the Ob one hundred miles above Obdorsk - Voykar Samoyeds.

However, nomadic reindeer herding provided economic independence, important in military and politically mobility and high level of self-awareness of the tundra Nenets, which even after the establishment of nominal Russian rule allowed them to maintain relative independence. This circumstance became very clear at the beginning of the 18th century, when the mass Christianization of the population of Western Siberia began: the Nenets (together with the Obdor Khanty reindeer herders) not only themselves did not accept the new faith, but also brutally persecuted the newly baptized Khanty and Mansi on the Lower Ob, Lyapin, Kunovat , Kazyme. The independence of the Nenets, their desire to completely get rid of foreign domination was certainly reflected in the insurrectionary movement of the Obdor Nenets and Khanty under the leadership of Vauli Piettomina in 1839-1841, although social and personal motives were apparently of no small importance here.

By the end of the 19th century, be that as it may, a relative balance had been established between the tundra Nenets and the Russian authorities, which was greatly facilitated by the fact that national policy The Russian state at least did not contradict the interests of the social elite of Nenets society, and the gradual development of capitalist commodity relations did its job in the tundra. The 1897 census recorded more than 6 thousand European tundra Nenets, about 5 thousand Siberian tundra and about 0.5 thousand Siberian forest ones. V.I. Vasiliev reasonably considered these figures to be incomplete. The total number of Nenets at the end of the 19th century can thus be estimated at no less than 12 thousand people. According to the Soviet census of 1926, there were 17 thousand of them.

Establishment Soviet power and the first Soviet years did not greatly affect the life of the Nenets. In 1929-1931, during the creation of national-territorial administrative units (national districts), the Nenets lands were divided into three parts: Nenets (with its center in Naryan-Mar), Yamalo-Nenets (Salekhard) and Dolgano-Nenets (Dudinka) were formed. national districts. In addition, part of the European Nenets turned out to be assigned to the Komi Republic, and part of the Siberian forest Nenets - to the Khanty-Mansi National Okrug. The transformations that began in the thirties (collectivization, “dekulakization,” “cultural revolution,” which for the natives of the North meant, first of all, the forcible removal of children from their parents and their placement in boarding schools) could not but lead to protest, the most striking manifestations of which were the uprising on Kazym in 1931-1934, in which the Forest Nenets took part together with the Khanty (see section on the Khanty), and the uprising of the Yamal Nenets (“ mandalada" - nen. m?nd?l??a"gathering, riot") in 1934. Open performances of the Nenets continued throughout the 30s, the last “ mandalada"was provoked by the OGPU in 1943. Despite the brutal suppression of protests, the destruction of the most active representatives of the people, the Soviet “transformations” had only external success in the tundra, the Nenets managed to sufficiently preserve their traditional way of life, culture and language. The preservation of the language, of course, was facilitated by the fact that since the 1930s the Nenets written language was created and a unified language standard for the tundra dialect was gradually introduced, which, in turn, was ensured by the proximity of the Nenets dialects from Kanin to Taimyr.

Only in the 80-90s of the 20th century did the Nenets begin to feel an increase in negative trends in the loss of cultural traditions and language - primarily in connection with the “successes” in the organization of boarding school education (see above, also in the section on the Khanty) and with the advancement oil to the Nenets tundra? and gas production. However, today the Nenets remain the most numerous of the small peoples of Siberia (in 1989 there were 34.2 thousand people in Russia) with almost the highest level of knowledge of their language (26.5 thousand - about 78% - Nenets named the Nenets language relatives in 1989).

Galina Podolyanets

"Nenets and their traditions." Materials and tasks for work on the implementation of the national component

We live in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. We came to this northern land from different parts of the country. They call it “a harsh land”, “the edge of the Earth”, “a sacred country where a good spirit cannot reach and an evil spirit cannot reach...” (from a Khanty song).

Exercise:

If you were asked to draw the “harsh edge of the Earth,” what would you depict (children are asked to verbally formulate an associative series).

Task:

development of imagination, ability to find verbal descriptions.

In ancient times, people lived in the snowy tundra near cold rivers. They went hunting, fished, and raised deer. They had everything necessary for life: they built houses from wood and deer skins, made tools, dishes, and sewed clothes. These kind, beautiful people still live next to us - these are the Nenets. They are the masters of this land, and we are the guests. The Nenets consider a handsome person to be someone “who has a face as round as the moon, a nose like a button, eyes like they don’t exist at all.”

The Nenets have long had special rules of life. The younger generation learned about them through legends from the elderly. A legend is a poetic legend. The Nenets sacredly cherished the legends they heard and told them to their children. Therefore, to this day there are strict rules in relation to nature, animals, humans, good and evil spirits. The rules that people have followed for centuries are also called traditions. Thanks to these traditions, the life of the Nenets is very different from ours.

For the Nenets, home is the entire visible tundra - the land on which they build their homes and graze reindeer. The walls of the house are considered to be the sea, mountains and forest. Beyond this lies a foreign land. From here, important rule: Don't harm your home. You cannot destroy vegetation, kill animals unnecessarily, or litter the tundra. The Nenets believe that nature is endowed with good and evil spirits Therefore, if a Nenets goes hunting, he always brings some kind of gift to the owner of the tundra.

Demonstration of the layout of the plague.

The tundra is a big home for the Nenets, but there is also a small one - this is chum. Chum is a Nenets dwelling. It's very convenient. The Nenets are a people who often move across the tundra and for convenience they need collapsible housing. Chum is a simple cone-shaped structure consisting of several poles and tires sewn from deer skins. In the center of the plague is a hearth. There is an iron circle under the fire, it closes the passage from the world of the dead to the tent. In the upper part there is a hole through which smoke from the fire escapes and, they say, through it spirits enter the tent. Good spirits, if the person has not done anything wrong. Hence, the second rule: it will always be good in your home if you do well.

The tent is warm, cozy, clean. Each thing knows its place, mostly they are all in the bags that the woman sews. The Nenets have a rule: It is clean not where they clean, but where they do not litter.

The Nenets believe that every thing has its own soul; having been with one person, it gets used to it, but may offend another. Hence, a strict covenant: do not steal, otherwise you will be severely punished.

Mystery:

Satisfy your hunger with mosses

At least the blizzard covered them.

Like shovels, horns

We are shoveling snow. (Deer)

The Nenets have a special attitude towards animals. The most revered is the deer, because the deer is food, housing, and transport. The Nenets make tents from reindeer skin, sew warm clothes, and reindeer meat is considered very healthy. The Nenets travel across the tundra on reindeer. They say that they used to ride reindeer on horseback, but now they are harnessed to wooden sleighs; the Nenets call them sledges. It turns out that deer have saved people more than once. If a Nenets is caught in a snowstorm in the tundra and gets lost, you can rely on the reindeer, he will definitely lead the team to his home.

Nenets riddle:

Two heads look to the sky. (Sled)

Mystery:

The owner of the forest

Wakes up in the spring

And in winter, under the blizzard howl

He sleeps in a snow hut. (Bear)

According to legend, the tundra is ruled by two owners - the Naked Bear and the Seven-Child Bear. The first is the leader of all polar bears; he lives in the sea and never goes onto land. The second is the bear, the leader of all brown bears, never leaves the hidden den. The Nenets fear and respect the bear. After all, encounters with a bear do not happen “just like that.” If you meet a bear or its trace, expect something unusual in your fate. Bears often help lost Nenets; legend says that the image of a bear appears and shows the way. The bear can also punish if a person made some kind of oath and did not keep it. If a person wears a bear fang on his belt, nothing will ever happen to him. The Nenets raise white deer especially for bears. When the deer turns seven years old, it is brought to the spirit of the bear in special places in the tundra.

Mystery:

Lies - silent

If you come up, he will grumble

Who goes to the owner

It lets you know. (Dog)

A dog is a man's faithful friend. The Nenets always have several dogs on their farm: some guard the tent, others guard the reindeer, and others help in hunting. The Nenets believe that the barking of a dog warns of the approach of evil spirits.

The Nenets legend tells how the Earth and the people on it appeared.

“At first there was only water. The sacred bird Loon took a piece of silt from the bottom and gave it to the Supreme Deity Num. From this silt Num molded the earth. Num created the sun and melted the glacier. Nga created the moon. When people came to life, Nga decided to breathe souls into them, but Num did not allow him to do this alone and they breathed in together, and since then they have coexisted in man - good and evil.”

The most important Deity among the Nenets is God Num. He controls the entire world where people live. And under seven layers of permafrost lives the terrible Nga, he and his underground spirits send damage and disease to people.

“In the summer there is a fight between the light and dark gods, sparks fly from the teeth with which they grab each other and people see lightning, and thunder is heard from the blows inflicted.”

Only a shaman can communicate with good and evil spirits. He lives in a separate tent, with the help of spirits he helps a person in hunting, farming, heals people, takes care of deer, and can even punish a person for committing a sin. The shaman addresses the spirits with the help of a mallet and a tambourine. The shaman knows spells and songs - calls to spirits, he dances around the fire, beats a tambourine and says: “Goy, goy, goy.” In response to his call, spirits flock to whom the shaman turns and fulfill his request.

In a Nenets family there are rules in the division of activities. A man, for example, must hunt, take care of deer, and fish. Children are allowed to play, boys, however, only outside the chum: they shoot arrows from a toy bow, which they make themselves, and learn to throw a noose around the neck of a deer. Girls play in the tent, their dolls are special. They are made from rags, and instead of a head there is a bird's beak, and the girl is also learning needlework.

A woman keeps order in the tent; she prepares dinner, sews clothes and bags from reindeer fur.

Shoes, clothes, pieces of fabric, and dry food are stored in bags. Nenets women say: “We women have a hundred knots, a thousand knots: you tie one knot, you untie another.” For the wedding, a girl must sew a lot of bags; if the bag is beautiful, then the girl is a good housewife and craftswoman. The craft bag has a special pocket for needles and a confidant decorated with a pattern. The bag is also decorated with metal objects; their jingling sounds ward off evil spirits.

A woman sews a pincushion from cloth and decorates it with beads and fur. The pincushion is endowed magical power. On it they flew over the taiga and swam across the seas.

Winter clothes and shoes are made from reindeer skins and the product is decorated with ornaments. Ornament is a repeating pattern on a product. The ornament is made from dark and light deer fur. The patterns are cut and sewn together to create a double mirror pattern. The combination of various parts of the ornament is called a mosaic.

Exercise:

Connect, ornament (children are invited to create a Nenets ornament from the elements). If the pattern is sewn onto clothing, it is already an applique.

Task:

introduction to the mosaic technique.

The ornament consists of various geometric shapes: rhombuses, squares, stripes, but they all form a certain symbol that can be “read”. Usually the woman took its name from nature: “hare ears”, “deer antlers”, “fox elbow”, “running sable”, etc. The ornament looks like an animal, and therefore it is sung in the Nenets song that on the Nenets fur coat An animal, a deer, is running.

The Nenets woman loves to make ornaments from beads; she strings them on a thread and produces magnificent beaded stripes for decorating clothes and shoes. There is a legend: “Once upon a time, long ago, overseas merchants sailed on the sea, sailed for a long time. We landed on the shore. They made a fire and, to shelter the fire from the wind, covered the fire with bags of soda. We sat by the fire for a long time and fell asleep. The next morning, when they woke up, they saw glass pieces that were formed from soda, fire, and wind. These multi-colored glass pieces were brought to the Nenets and they began to weave jewelry from them.”

Exercise:

Read the ornament (children are asked to name the ornament of the proposed bead strips).

Task:

teach children to identify the uniqueness of the Nenets ornament.

The question of a son's marriage was usually decided by the father, in consultation with his other sons. Wedding ceremony The Nenets included matchmaking, payment of kalym (most often in deer), and a wedding feast, first in the bride’s camp, then in the groom’s camp. Among wealthy reindeer herders, polygamy occurred.

In the spiritual life of the Nenets, there is syncretism (mixing) of Christian and pagan ideas. Thus, the supreme deity of the Nenets Num acquires the features of a Christian god. Saint Nicholas is included in the pantheon of master spirits in the form of Syadai-Mikola, the patron saint of crafts. The Nenets celebrated a number of Christian holidays, wore Orthodox crosses, and icons became common in the interior of their homes.

In general, faith in spirits dominated religious beliefs. Num, who lived in heaven, was considered the creator of all life on earth, and Ya was the mistress of the earth. The evil principle was personified by Nga, the ruler of the underworld. There were owners of forests, mountains, rivers, etc., to whom the Nenets, going hunting, made sacrifices. Spirits were depicted from wood, stone, and bone in the form of dolls (idols), which were sometimes dressed in miniature clothes.

Shamans played the role of intermediaries between spirits and people. They were contacted in case of illness, “harvest failure” of arctic foxes, poor catch of fish or calving of deer. Each shaman had a tambourine with a handle on the inside and other attributes. Special costumes and an iron crown were preserved only among the Yenisei Nenets. The shaman was usually present at the ritual of seeing off a deceased person to the afterlife.

The Nenets buried them either in shallow holes, covering them with boards and covering them with earth, or in boxes on the surface of the ground. The deceased’s deer were killed in the cemetery, and his personal belongings were left behind, having previously been damaged. It was believed that in the other world they would be restored and serve their former master. A trochee pole with a bell tied to it was strengthened next to the grave to scare away evil spirits.

Nenets art is represented by fur mosaics (from dark and white), which decorated outerwear, hats, and some household items (for example, bags). Weaving of ornaments from braid and multi-colored threads, embroidery with deer hair, and ornamental wood and bone carvings are developed.

Oral folk art The Nenets are represented by heroic songs (syudbabts), plot stories (yarabts), historical legends, fairy tales (vadako, lahnaku), and riddles. A very common genre was lyrical improvisation songs (hynbats).

As musical instruments The Nenets used a playing bow (struck with an arrow), a playing sinew, a two-string bowed lute, various whistles and tweeters.