What happened before the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet. Glagolitic is an ancient Slavic alphabet. Ancient Slavic writing systems

Glagolitic and Cyrillic- ancient Slavic alphabet. The origin of the Glagolitic alphabet remains a matter of debate. Attempts to bring the Glagolitic alphabet closer to Greek cursive (minuscule writing), Hebrew, Coptic and other writing systems did not yield results. Glagolitic, like the Armenian and Georgian script, is an alphabet that is not based on any known writing system. The letterforms correspond to the task of translating Christian texts into the Slavic language. The first letter of the alphabet has the shape of a cross, the abbreviated spelling of the name of Christ forms a symmetrical figure, etc. Some researchers believe that the Glagolitic letters are based on the cross, triangle and circle - the most important symbols of Christian culture.

The Cyrillic alphabet is based on the Byzantine charter letter. To convey sounds that were absent in the Greek language, letters borrowed from other sources (, ,) were used.

The question of which of these alphabets is the oldest has not been finally resolved, but most researchers believe that Cyril created the Glagolitic alphabet, while the Cyrillic alphabet has a later origin. Among the facts confirming this opinion are the following.

1. The oldest Glagolitic manuscripts come from those areas where Cyril and Methodius worked (Moravia) or their disciples expelled from Moravia (southwestern regions of the Bulgarian kingdom). The oldest Cyrillic texts were written in the east of the Balkan Peninsula, where there was no direct influence of the Solun brothers.

1. The oldest Glagolitic manuscripts come from those areas where Cyril and Methodius worked (Moravia) or their disciples expelled from Moravia (southwestern regions of the Bulgarian kingdom). The oldest Cyrillic texts were written in the east of the Balkan Peninsula, where there was no direct influence of the Solun brothers.

2. Glagolic monuments are more archaic in language.

3. There are errors in Cyrillic texts, indicating that the text was rewritten from the Glagolitic original. There is no evidence that Glagolitic manuscripts could have been copied from Cyrillic ones.

4. Parchment - the writing material of the Middle Ages - was quite expensive, so they often resorted to writing new text in old book. The old text was washed off or scraped off, and a new one was written in its place. Such manuscripts are called palimpsests. There are several known palimpsests where the Cyrillic text is written in the washed-out Glagolitic alphabet, but there are no Glagolitic texts written in the washed-out Cyrillic alphabet.

If the Glagolitic alphabet was created by Cyril, then the Cyrillic alphabet, in all likelihood, was created in Eastern Bulgaria by the Preslav scribes. Almost everywhere the Cyrillic alphabet has replaced the Glagolitic alphabet. Only the Croats living on the islands of the Adriatic Sea used Glagolitic liturgical books until recently.

The Cyrillic alphabet is used by those of the Slavic peoples who professed Orthodoxy. Writing based on the Cyrillic alphabet is used by Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Macedonians. In the 19th-20th centuries. missionaries and linguists based on the Cyrillic alphabet created writing systems for the peoples living on the territory of Russia.

The Cyrillic alphabet is used by those of the Slavic peoples who professed Orthodoxy. Writing based on the Cyrillic alphabet is used by Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Macedonians. In the 19th-20th centuries. missionaries and linguists based on the Cyrillic alphabet created writing systems for the peoples living on the territory of Russia.

In Russia, the Cyrillic alphabet has undergone a certain evolution. Already by the 12th century. letters are falling out of use. At the beginning of the 18th century. Peter I carried out a spelling reform, as a result of which the letters of the Cyrillic alphabet acquired new styles. A number of letters (, etc.) were excluded, the sound meaning of which could be expressed in a different way. From that time on, secular publications were typed in the reformed alphabet, and church books in traditional Cyrillic. In the middle of the 18th century. the letter E was added to the civil seal, and in 1797 N.M. Karamzin introduced the letter E. His modern look The Russian alphabet received as a result of the spelling reform of 1918, as a result of which the letters were excluded n, q. In the mid-1930s, it was planned to create a new Russian alphabet on a Latin basis. However, this project was not implemented.

But among researchers in the 20th century, the opposite opinion was firmly established and now prevails: the creator of the Slavic alphabet invented not the Cyrillic alphabet, but the Glagolitic alphabet. It is she, the Glagolitic alphabet, that is ancient, first-born. It was in its completely unusual, original lettering that the oldest Slavic manuscripts were executed.Following this conviction, they believe that the Cyrillic alphabet tradition was established later, after the death of Cyril, and not even among the first students, but after them - among writers and scribes who worked in the Bulgarian kingdom in the 10th century. Through them, as is known, the Cyrillic alphabet was transferred to Rus'.

It would seem that if the authoritative majority gives primacy to the Glagolitic alphabet, then why not calm down and return to an outdated issue? However, the old topic comes up again and again. Moreover, these impulses most often come from Glagolitic lawyers. You might think that they intend to polish some of their almost absolute results to a shine. Or that they are still not very calm in their souls, and they are expecting some unexpected daring attacks on their system of evidence.

After all, it would seem that everything in their arguments is very clear: the Cyrillic alphabet replaced the Glagolitic alphabet, and the displacement took place in rather crude forms. There is even a date indicated from which it is proposed to count the forceful elimination of the Glagolitic alphabet and its replacement with the Cyrillic alphabet. For example, according to the conviction of the Slovenian scientist Franz Grevs, it is recommended to consider the period 893-894 as such a date, when the Bulgarian state was headed by Prince Simeon, himself half-Greek by origin, who received an excellent Greek education and therefore immediately began to advocate for the establishment of an alphabet within the country, its alphabetic graphics vividly echo, and for the most part coincide with, the Greek letter.

Both politics and personal whim supposedly interfered with cultural creativity at the same time, and this looked like a disaster. Entire parchment books in a short period of time, mainly dating back to the 10th century, were hastily cleared of Glagolitic writing, and on the washed sheets a secondary record appeared everywhere, already written in Cyrillic statutory handwriting. Monumental, solemn, imperial.

Letter historians call rewritten books palimpsests. Translated from Greek: something freshly written on a scraped or washed sheet. For clarity, you can recall the usual blots in a school notebook, hastily erased with an eraser before entering a word or letter in the corrected form.

Abundant scrapings and washes of Glagolitic books seem to be the most eloquent of all and confirm the seniority of the Glagolitic alphabet. But this, we note, is the only documentary evidence of the forceful replacement of one Slavic alphabet with another. The most ancient written sources did not preserve any other reliable evidence of the cataclysm. Neither the closest disciples of Cyril and Methodius, nor their successors, nor the same Prince Simeon, nor any other contemporaries of such a notable incident considered it necessary to speak out about it anywhere. That is, nothing: no complaints, no prohibitory decree. But the persistent adherence to Glagolitic writing in the atmosphere of polemics of those days could easily have raised accusations of heretical deviation. But - silence. There is, however, an argument (it was persistently put forward by the same F. Grevs) that the Slavic writer of the early 10th century, Chernorizets the Brave, acted as a brave defender of the Glagolitic alphabet in his famous apology for the alphabet created by Cyril. True, for some reason the Brave himself does not say a word or a hint about the existence of an elementary conflict. We will definitely turn to an analysis of the main provisions of his apology, but later.

In the meantime, it doesn’t hurt to once again record the widespread opinion: the Cyrillic alphabet was given preference only for reasons of political and cultural etiquette, since in most alphabetic spellings it, we repeat, obediently followed the graphics of the Greek alphabet, and, therefore, did not represent any extraordinary challenge to the written tradition Byzantine ecumene. The secondary, openly pro-Greek alphabet was supposedly the people who established its priority, named in memory of Cyril the Philosopher.

This strange research discrepancy, we agree, greatly devalues the arguments of supporters of the Glagolitic alphabet as the absolute and only brainchild of Cyril the Philosopher. And yet, the existence of palimpsests has forced and will force everyone who touches the topic of the primal Slavic alphabet to check the logic of their evidence again and again. The initial letters of the parchment books, which were not completely cleaned, can still be recognized, if not read. No matter how much the parchment sheets are washed, traces of the Glagolitic alphabet still appear. And behind them, it means, either crime appears, or some kind of forced necessity of that distant time.

Fortunately, the existence of the Glagolitic alphabet today is evidenced not only by palimpsests. IN different countries a whole corpus of ancient written monuments of Glagolitic alphabetic graphics has been preserved. These books or their fragments have long been known in science and have been thoroughly studied. Among them, first of all, it is necessary to mention the Kyiv sheets of the 10th – 11th centuries. (the monument is kept in the Central Scientific Library of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv), Assemani Gospel of the 10th – 11th centuries. (in the Slavic department of the Vatican Library), Zograf Gospel of the 10th – 11th centuries. (in the Russian National Library, St. Petersburg), Mariinsky Gospel of the X – XI centuries. (in Russian State Library, Moscow), Klotsiev collection of the 11th century. (Trieste, Innsbruck), Sinai Psalter of the 11th century. (in the Library of the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai), Sinai Breviary of the 11th century. (ibid.).Let us limit ourselves to at least these, the most ancient and authoritative ones. All of them, as we see, do not belong to firmly dated monuments, since none of them preserved records with an exact indication of the year of creation of the manuscript. But even rounded, “floating” dates, without saying a word, confirm: all manuscripts arose after the death of the founders of Slavic writing. That is, at a time when, according to the supporters of the “glagolic primacy,” the tradition of this letter was intensively supplanted by adherents of the pro-Greek alphabet, which allegedly prevailed contrary to the intentions of the “glagolitic” Cyril.

The conclusion that inexorably suggests itself: the dating of the oldest Glagolitic sources in themselves does not allow us to overdramatize the picture of the confrontation between the first two Slavic alphabets. Note that several of the oldest Cyrillic manuscripts date back to the 11th century. Ancient Rus': these are the world-famous Reims Gospel of the first half of the century, the Ostromir Gospel of 1056-1057, the Izbornik of Svyatoslav of 1073, the Izbornik of Svyatoslav of 1076, the Archangel Gospel of 1092, Savin’s book - all, by the way, on clean sheets, without traces of washing.

So excessive dramatization is also inappropriate in the issue of palimpsests. For example, a careful study of the pages of the Glagolitic Zograf Gospel repeatedly reveals traces of washing or erasing of the old text and new writings in their place. But what’s on the pages washed clean of the Glagolitic alphabet? Glagolitic again! Moreover, the largest of these restorations (we are talking about an entire notebook from the Gospel of Matthew) dates back not to the 10th – 11th centuries, but to the 12th century.

This manuscript also contains Cyrillic text. But he modestly appears only on the pages of its additional part (the synaxarion). This section already applies to XIII century and the text is printed on clean sheets, not washed from the Glagolitic alphabet. In an article devoted to the Zograf Gospel (Kirilo-Metodievskaya Encyclopedia volume 1, Sofia, 1985), Bulgarian researcher Ivan Dobrev mentions that in 1879 the Glagolitic, that is, the oldest part of the monument was published in Cyrillic transliteration. This created the basis for a more careful scientific analysis of the two alphabets. Acquaintance with the original was also simplified for readers who were deprived of the opportunity to read the Glagolitic alphabet, forgotten over the past centuries. In any case, this method of accessing an ancient source cannot be confused with washing or scraping.

Of the surviving ancient manuscripts, perhaps only the only one can be classified as completely washed out of the Glagolitic alphabet. This is the Cyrillic Boyana Gospel of the 11th century. It inevitably acquired somewhat odious fame, as clear evidence of the harsh displacement of one tradition in favor of another. But all the oldest monuments of Glagolitic writing listed above testify to something else - the peaceful coexistence of two alphabetic traditions at the time of the construction of a single literary language Slavism.

As if in fulfillment of the oral covenant of their teachers, the successors of the work of Cyril and Methodius came to an unspoken agreement. Let’s try to boil it down to the following: since the Slavs, unlike other inhabitants of the earth, are so lucky that their written language is created using two alphabets at once, then there is no need to get too excited; let these ABCs try their best, proving their abilities, their best properties, their ability to be remembered more easily and reliably, to enter the depths of human consciousness, to cling more firmly to visible things and invisible meanings. It took several decades, and it began to emerge that competition was not an idyll after all. It cannot go on equal terms for too long.

Yes, Glagolitic writing, having achieved considerable success at the first stage

the construction of a new literary language, having initially struck the imagination of many with its freshness, unprecedentedness, bright and exotic novelty, its mysterious appearance, the clear correspondence of each individual sound to a certain letter, gradually began to lose ground. In the Glagolitic syznachal there was the quality of a deliberate, deliberately closed object, suitable for a narrow circle of initiates, owners of almost secret writing. In the appearance of its letters, some kind of playfulness and curliness appeared every now and then, simple manipulations flashed every now and then: turned it up in circles - one letter, down in circles - another, in circles to the side - a third, added a similar side next to it - a fourth... But the alphabet as such in the life of the people who use it cannot be the subject of a joke. Children feel this especially deeply, as they complete the first letters and syllables in their notebooks with great attention and almost prayerful effort of all their strength. The ABC is too closely connected with the main meanings of life, with its sacred heights, to wink at the reader. An illiterate shepherd or farmer, or warrior, stopping at a cemetery slab with large incomprehensible letters, despite his ignorance, still read: something most important is expressed here about the fate of a person unknown to him.

Another reason why there is still no peace around the issue of the Glagolitic alphabet is that the further we go, the more the prospect of the very origin of the phenomenal alphabetic doctrine begins to waver. Its appearance still excites the imagination of researchers. Competitive activity in finding more and more evidence-based guesses does not dry out. It is pretentiously called the sacred code, the matrix of universal sound, to which it is necessary, as to a great sanctuary, to open both the Cyrillic alphabet and other European alphabets. Who will have the honor of finally revealing the pedigree of the outlandish guest at the feast of letters?

The tangle of scientific, and more recently amateur, hypotheses is growing before our eyes. Their volume today has become such that experts on the issue seem to be already in dismay at the sight of the non-stop chain reaction version creation. And many people wonder: isn’t it time to finally stop and agree on one thing? Otherwise, the topic of the genesis of the Glagolitic alphabet will one day choke in the funnel of evil infinity. Last but not least, it is confusing that in the confusion and confusion of disputes about the origin of names, not very attractive methods of disputing authorities are often discovered.

Clearly, science is not dispassionate. In the heat of intellectual battles, there is no shame in insisting on your own to the end. But it is awkward to observe how other people’s arguments are deliberately forgotten and generally known written sources or dates are ignored. Just one example. A modern author, describing in a popular scientific work the Reims Gospel, taken by the daughter of Prince Yaroslav the Wise Anna to France, calls it a Glagolitic monument. And for greater persuasiveness, he places an image of a passage written in Croatian handwriting in the style of the Gothic Glagolitic alphabet. But the manuscript of the Reims Gospel, as is well known in scientific world, consists of two parts that are very unequal in age. The first, oldest, dates back to the 11th century and is made in Cyrillic writing. The second, Glagolitic, was written and added to the first only in the 14th century. At the beginning of the 18th century, when Peter the Great was visiting France, the manuscript, as a precious relic, on which the French kings swore allegiance, was shown to him, and the Russian Tsar immediately began to read aloud the Cyrillic verses of the gospel, but was puzzled when it came to the Glagolitic part.

The 20th century Bulgarian scientist Emil Georgiev once set out to compile an inventory of the variants of the origin of the Glagolitic alphabet existing in Slavic studies. It turned out that as a model for it, different authors in different time the most unexpected sources were proposed: archaic Slavic runes, Etruscan script, Latin, Aramaic, Phoenician, Palmyrene, Syriac, Hebrew, Samaritan, Armenian, Ethiopian, Old Albanian, Greek alphabetic systems...

This extreme geographical dispersion alone is puzzling. But Georgiev’s inventory of half a century ago, as is now obvious, needs additions. It does not include references to several more new or old, but half-forgotten investigations. Thus, it was proposed to consider the Germanic runic writing as the most reliable source. The model for the Glagolitic alphabet could, in another opinion, be the alphabetic production of Celtic missionary monks. Recently, the arrow of search from the west again sharply deviated to the east: Russian researcher Geliy Prokhorov considers the Glagolitic alphabet to be a Middle Eastern missionary alphabet, and its author is the mysterious Constantine the Cappadocian, the namesake of our Constantine-Cyril. Reviving the ancient tradition of the Dalmatian Slavs, as the sole creator of the Glagolitic alphabet, they again started talking about Blessed Jerome of Stridon, the famous translator and systematizer of the Latin “Vulgate”. Versions of the emergence of the Glagolitic alphabet under the influence of the graphics of the Georgian or Coptic alphabets have been proposed.

E. Georgiev rightly believed that Constantine the Philosopher, by his temperament, could in no way resemble a collector of Slavic alphabetic treasures from the world. But still, the Bulgarian scientist simplified his task by repeatedly stating that Kirill did not borrow anything from anyone, but created a completely original letter, independent of external influences. At the same time, with particular fervor, Georgiev protested the concept of the origin of the Glagolitic alphabet from Greek cursive writing of the 9th century, proposed back in late XIX century by the Englishman I. Taylor. As is known, Taylor was soon supported and supplemented by the Russian professor from Kazan University D. Belyaev and one of the largest Slavists in Europe V. Yagich, who formulated the role of Kirill as the creator of the new alphabet extremely succinctly: “der Organisator des glagolischen Alfabets.” Thanks to Yagich’s authority, Georgiev admits, the theory “has gained enormous popularity.” Later, A. M. Selishchev joined the “Greek version” in his capital “Old Slavonic language”. Princeton scholar Bruce M. Metzger, author of the study “Early Translations of the New Testament” (Moscow, 2004), is cautiously inclined towards the same opinion: “Apparently,” he writes, “Cyril took as a basis the intricate Greek minuscule letter of the 9th century. , may have added a few Latin and Hebrew (or Samaritan) letters...". The German Johannes Friedrich speaks in approximately the same way in his “History of Writing”: “... the most probable origin of the Glagolitic alphabet seems to be from the Greek minuscule of the 9th century...”.

One of Taylor's main arguments was that the Slavic world, thanks to its centuries-old connections with Hellenistic culture, had an understandable attraction to Greek writing as a model for its own book structure and did not need to borrow from the alphabets of the eastern version for this. The alphabet proposed by Cyril the Philosopher was supposed to proceed precisely from taking into account this counter-thrust of the Slavic world. There is no need to analyze E. Georgiev’s counter-arguments here. It is enough to recall that the main one has always been unchanged: Konstantin-Kirill created a completely original letter that did not imitate any alphabets.

Complementing Taylor's developments, Yagich also published his own comparative table. On it, Greek cursive and minuscule letters of that era are side by side with Glagolitic alphabet (rounded, so-called “Bulgarian”), Cyrillic alphabet and Greek uncial script.

Looking at Yagich's table, it is easy to notice that the cursive Greek italic (minuscule) located on the left of it, with its smooth curves, now and then echoes the Glagolitic circular signs. The conclusion involuntarily suggests itself about the flow of letter styles of one alphabet into the neighboring one. So this is not true?

Something else is more important. Peering at the Greek cursive of the 11th century, we seem to be half a step closer to Constantine’s desk, we see excited, quick notes on the topic of the future Slavic letter. Yes, these are, most likely, drafts, the first or far from the first working estimates, sketches that can be easily erased in order to correct them, like erasing letters from a school wax tablet or from a smoothed surface of damp sand. They are light, airy, cursive. They do not have the solid, intense monumentality that distinguishes the Greek solemn uncial of the same period.

Working Greek italics, as if flying from the pen of the brothers, the creators of the first Slavic literary language, seem to return us again to the setting of a monastic monastery at one of the foothills of Mount Lesser Olympus. We remember this silence of a very special nature. It is filled with meanings that, by the end of the fifties of the 9th century, were first identified in the contradictory, confusing Slavic-Byzantine dialogue. In these senses it was clearly read: the hitherto spontaneous and inconsistent coexistence of two great linguistic cultures– Hellenic and Slavic – is ready to be resolved into something still unprecedented. Because, as never before, their long-standing attention to each other, at first childishly curious, and then more and more interested, was now evident.

It has already been partly said that the Greek classical alphabet within the ancient Mediterranean, and then in the wider Euro-Asian area for more than one millennium, represented a cultural phenomenon of a very special attractive force. The Etruscans began to feel attracted to him as a role model. Even if the vocalization of their written characters is still not sufficiently revealed, the Latins, who replaced the Etruscans in the Apennines, successfully imitated two alphabets to create their own writing: both Greek and Etruscan.

There is nothing offensive in such imitations. Not all nations enter the arena of history at the same time. After all, the Greeks, in their laborious, centuries-long efforts to complete their writing, initially used the achievements of the Phoenician alphabetic system. And not only her. But in the end they made a real revolution in the then practice of written speech, for the first time legitimizing separate letters for vowel sounds in their alphabet. Behind all these events, it was not suddenly discovered from the outside that the Greeks were also the creators of grammatical science, which would become a model for all neighboring peoples of Europe and the Middle East.

Finally, in the age of the appearance of Christ to humanity, it was the Greek language, enriched by the experience of translating the Old Testament Septuagint, that took upon itself the responsibility of becoming the first, truly guiding language of the Christian New Testament.

In the great Greek gifts to the world, out of habit, we still keep in first place antiquity, the pagan gods, Hesiod and Homer, Plato and Aristotle, Aeschylus and Pericles. Meanwhile, they themselves have humbly gone into the shadow of the four evangelists, the apostolic epistles, the grandiose vision on Patmos, the liturgical works of John Chrysostom and Basil the Great, the hymnographic masterpieces of John of Damascus and Romanus the Sweet Singer, the theology of Dionysius the Areopagite, Athanasius of Alexandria, Gregory Palamas.

Less than a century after the Gospel events, various peoples of the Mediterranean longed to learn the Holy Scriptures in their native languages. This is how early experiments in translating the Gospel and the Apostle into Syriac, Aramaic, and Latin appeared. A little later, the inspired translation impulse was picked up by the Coptic Christians of Egypt, the Armenian and Georgian churches. At the end of the 4th century, a translation for Gothic Christians, made by the Gothic Bishop Wulfila, declared its right to exist.

With the exception of the Syrian-Assyrian manuscripts, executed using the traditional Middle Eastern alphabet series, all the rest in their own way showed respect for the alphabetical structure of the Greek primary sources. In the Coptic alphabet of Christian translations, which replaced the ancient hieroglyphic writing of the Egyptians, 24 letters imitate the Greek uncial in their styles, and the remaining seven were added to record sounds unusual for Greek speech.

A similar picture can be seen in the Gothic Silver Codex, the most complete manuscript source with the text of Wulfila's translation. But here a number of Latin letters are added to the Greek letters, and in addition, signs from Gothic runes are added for sounds external to Greek articulation. Thus, the newly created Gothic and Coptic alphabets each in their own way complemented the Greek letter base - not to its detriment, but not to their own detriment. Thus, in advance, an easier way was provided for many generations in advance to get acquainted - through the accessible appearance of letters - with the very neighboring languages of the common Christian space.

When creating the Armenian and then Georgian alphabets, a different path was chosen. Both of these Caucasian scripts without hesitation adopted the alphabetical sequence of the Greek alphabet as a basis. But at the same time they immediately received new original graphics of an oriental style, outwardly in no way reminiscent of the writing of the Greeks. Academician T. Gamkrelidze, an expert on Caucasian ancient written initiatives, notes about this innovation: “From this point of view, ancient Georgian writing Asomtavruli, ancient Armenian Yerkatagir and Old Slavonic Glagolitic fall under a general typological class, contrasting Coptic and Gothic writing, as well as Slavic Cyrillic, the graphic expression of which reflects the graphics of the contemporary Greek writing system.”

This, of course, is not an assessment, but a calm statement of the obvious. Gamkrelidze speaks more definitely when considering the works of Mesrop Mashtots, the generally recognized author of the Armenian alphabet: “The motive for such free creativity of graphic symbols of ancient Armenian writing and the creation of original written characters, graphically different from the corresponding Greek ones, should have been the desire to hide the dependence of the newly created writing on the written the source used as a model for its creation, in this case from Greek writing. In this way, an outwardly original national writing was created, as if independent from any external influences and connections.”

It is impossible to admit that Cyril the Philosopher and Methodius, representatives of the dominant Greek written culture, did not discuss with each other how Coptic and Gothic books differed in the nature of their alphabetic characters from the same Georgian and Armenian manuscripts. How impossible it is to imagine that the brothers were indifferent to the many examples of the Slavs’ interest not only in Greek oral speech, but also in Greek writing, its alphabetic structure and counting.

What path should they follow? It seems that the answer was implied: to build a new Slavic writing, using the Greek alphabet as a model. But are all Slavs necessarily unanimous in their reverence for the Greek letter? After all, in Chersonese, in 861, the brothers were leafing through a Slavic book, but written in letters that were different from Greek. Maybe the Slavs of other lands already have their own special views, their own wishes and even counter-offers? It is not for nothing that Constantine, two years later, during a conversation with Emperor Michael about the upcoming mission to the Great Moravian Principality, said: “... I will go there with joy, if they have letters for their language.” As we remember, the hagiographer, describing that conversation in the “Life of Cyril,” also cited the basileus’ evasive answer regarding the Slavic letters: “My grandfather, and my father, and many others looked for them and did not find them, how can I find them?” To which came the response of the younger Thessalonian, similar to a sorrowful sigh: “Who can record a conversation on the water?..”

Behind this conversation there is an internal confrontation that greatly confused Konstantin. Is it possible to find a letter for a people who have not yet looked for a letter for themselves? Is it acceptable to set off on a journey with something prepared in advance, but completely unknown to those you are going to? Will such an unsolicited gift offend them? After all, it is known - from the same appeal of Rostislav the Prince to Emperor Michael - that the Romans, the Greeks, and the Germans had already come to preach to the Moravans, but they preached and served services in their own languages, and therefore the people, the “simple children”, involuntarily remained deaf to incomprehensible speeches...

In the lives of the brothers there is no description of the embassy from Moravia itself. Neither its composition nor the duration of its stay in Constantinople is known. It is unclear whether Prince Rostislav's request for help was formalized in the form of a letter and in what language (Greek? Latin?) or whether it was only an oral message. One can only guess that the brothers still had the opportunity to find out in advance from the guests how similar their Slavic speech was to what the Solunians had heard since childhood, and how naive the Moravians were in everything related to communication in writing. Yes, as it turns out, it is quite possible to understand each other’s speech. But such a conversation is like ripples raised by the wind on the water. A church service is a completely different kind of interview. It requires written signs and books that are understandable to the Moravians.

Letters! Writing... What kind of letters, what kind of writing do they know and to what extent? Will the alphabetical and translation warehouse that the brothers and their assistants prepared for several years in a row in the monastery on Lesser Olympus, not yet knowing whether there will be a need for this work of theirs outside the walls of the monastery, will be sufficient for acquaintance of the Moravian Slavs with the holy books of Christianity.

And suddenly it was unexpectedly revealed: such a need is not a dream at all! Don’t worry about the whim of a small handful of monks and the Philosopher who came to them for an extended stay and captivated them with an unprecedented initiative.

But he himself, summoned together with Abbot Methodius to the basileus - what confusion he suddenly fell into! The books on the Small Olympus are already ready, and they read from them, and sing, and he, who worked the hardest, now seemed to back away: “... I’ll go if they have their own letters for writing there...”.

And if not, then we already have it! By himself, the Philosopher, the writings collected into alphabetical order, suitable and attractive for the Slavic ear and eye...

Isn’t it like this with any business: no matter how carefully you prepare, it still seems too early to announce it to people. A whole mountain of reasons is immediately found to delay further! And ill health, and the fear of falling into the sin of arrogance, and the fear of disgrace in an overwhelming task... But did they avoid overwhelming tasks before?

... Trying to imagine the internal state of the Thessaloniki brothers on the eve of their departure on a mission to the Great Moravian Principality, I essentially do not deviate from the meager hints on this topic set out in two lives. But clarifying the psychological motivations for this or that action of my heroes is not speculation at all! The need for conjecture, assumption, version arises when clues, even the most meager, are absent from the sources. And I simply need a working conjecture. Because it is lacking on the issue that forms the spring of the entire Slavic alphabet binary. After all, the lives, as already mentioned, are silent about which alphabet Methodius and Constantine took with them on their long journey. And although the prevailing belief today seems to leave no room for dissent, I am more and more inclined to the following: the brothers could not have brought with them what is called today the Glagolitic alphabet. They were carrying their original alphabet. The original one. That is, emanating in its structure from the gifts of the Greek alphabet. The same one that is now called Cyrillic. And they brought not only the alphabet, as such, but also their original books. They carried translation works written in the language of the Slavs using an alphabet modeled on the Greek alphabet, but with the addition of letters from the Slavic scale. The very logic of the formation of Slavic writing, if we are completely honest in relation to its laws, holds, does not allow us to stumble.

Glagolitic? She will make her presence known for the first time a little later. The brothers will deal with her upon arrival in Velehrad, the capital of the Moravian land. And, apparently, this will not happen in the year of arrival, but after the extraordinary events of the next year, 864. It was then that the East Frankish king Louis II the German, having concluded a military alliance with the Bulgarians, would once again attack the Great Moravian city of Devin.

The invasion, unlike the previous one undertaken by the king almost ten years ago, will be successful. This time Louis will force Prince Rostislav to accept humiliating conditions, essentially vassal conditions. From now on, the work of the Greek mission within the Great Moravian state will be under the sign of incessant pressure from Western opponents of Byzantine influence. In the changed circumstances, the brothers could have been helped by the forced development of a different alphabet graphics. One that, with its appearance, neutral in relation to the pro-Greek letter, would remove, at least in part, tensions of a jurisdictional and purely political nature.

No, there is no way to escape the thorny question of the origin of the Glagolitic alphabet. But now we will have to deal with a very small number of hypotheses. There are only two of them, minus the numerous eastern ones, three at most. They, among others, have already been mentioned above.

There are no overwhelming arguments either for or against the assumption that the Glagolitic alphabet came out of a Celtic monastic environment. In connection with this address, they usually refer to the work of the Slavist M. Isachenko “On the question of the Irish mission among the Moravian and Pannonian Slavs.”

Let’s say that a certain “Irish clue” worked for the Philosopher and his older brother. Let's say they found in it the necessary signs for purely Slavic sounds. (This means that both sides are going in the right direction!). And they even discovered that this Irish-style alphabetical sequence generally corresponds to the legal Greek alphabetical sequence. Then they, together with their employees, would quickly learn this letter, albeit an intricate one. And translate into his graphics the Slavic liturgical manuscripts already brought from Constantinople. Let their low-Olympic books, after creating lists from them in a new way, rest a little on the shelves or in the chests. At least there is a reason for a good joke in what happened! What kind of Slavs are these? Lucky for them!.. no one else in the world has ever written a letter in two alphabets at once.

An ancient but enduring legend looks weaker compared to the “Celtic” version: the supposed author of the Glagolitic alphabet is Blessed Jerome of Stridon (344-420). The legend is based on the fact that Jerome, revered throughout the Christian world, grew up in Dalmatia, in a Slavic environment, and himself may have been a Slav. But if Jerome was engaged in alphabetical exercises, then no reliable traces of his educational activities in favor of the Slavs remained. As is known, the work of translating into Latin and systematizing the corpus of the Bible, later called the Vulgate, required a colossal effort of all Jerome’s spiritual and humanitarian abilities.

The brothers knew firsthand the work that took several decades of the hermit’s life. They hardly ignored Jerome’s refined translation skills. This amazing old man could not help but be for them an example of spiritual asceticism, outstanding determination, and a treasure trove of technical translation techniques. If Jerome had left at least some sketch of the alphabet for the Slavs, the brothers would probably have happily begun to study it. But nothing remained except the legend of the blessed worker’s love for Slavism. Yes, they hardly heard the legend itself. Most likely, she was born in a close community of “Glagolish” Catholics, stubborn Dalmatian patriots of Glagolitic writing, much later than the death of Cyril and Methodius.

There remains a third option for the development of events in Great Moravia after the military defeat of Prince Rostislav in 864. I.V. Lyovochkin, a famous researcher of the manuscript heritage of Ancient Rus', writes in his “Fundamentals of Russian Paleography”: “Compiled in the early 60s of the 9th century. Constantine-Kirill the Philosopher, the alphabet well conveyed the phonetic structure of the language of the Slavs, including the Eastern Slavs. Upon arrival in Moravia, the mission of Constantine-Cyril was convinced that there already was a writing based on the Glagolitic alphabet, which was simply impossible to “cancel.” What could Constantine-Kirill the Philosopher do? Nothing but persistently and patiently introduce his new writing system, based on the alphabet he created - the Cyrillic alphabet. Complex in its design features, pretentious, having no basis in the culture of the Slavs, the Glagolitic alphabet, naturally, turned out to be unable to compete with the Cyrillic alphabet, which is brilliant in its simplicity and elegance...”

I would like to fully subscribe to this strong opinion about the determination of the brothers in defending their convictions. But what about the origin of the Glagolitic alphabet itself? The scientist believes that the Glagolitic alphabet and the “Russian letters” that Konstantin analyzed three years ago in Chersonesus are one and the same alphabet. It turns out that the brothers again had to deal with some already very widely spread writings - from Cape Chersonese in Crimea to the Great Moravian Velehrad. But if in Chersonesos Constantine treated the Gospel and Psalter shown to him with respectful attention, then why now, in Great Moravia, did the brothers perceive the Glagolitic alphabet almost with hostility?

Questions, questions... As if under a spell, the Glagolitic alphabet is in no hurry to let it approach its ancestry. Sometimes it seems like he won’t let anyone in anymore.

Is it time to finally call for help the author who wrote under the name Chernorizets Khrabr? After all, he is almost a contemporary of the Thessaloniki brothers. In his apologetic work “Answers about the Writings,” he testifies to himself as an ardent defender of the educational work of the Thessaloniki brothers. Although this author himself, judging by his own admission (it is read in some ancient lists of “Answers...”) did not meet the brothers, he was familiar with people who remembered Methodius and Cyril well.

Small in volume, but surprisingly meaningful, Khrabr’s work has grown to this day with a huge palisade of philological interpretations. This is no coincidence. Chernorizets Khrabr is also a philologist himself, the first philologist from the Slavic environment in the history of Europe. And not just any beginner, but an outstanding expert for his era in both Slavic speech and the history of Greek writing. Judging by the amount of his contribution to the venerable discipline, one can, without exaggeration, consider him the father of Slavic philology. Isn’t it worthy of surprise that such a contribution took place in the very first century of the existence of the first literary language of the Slavs! This is how rapidly the young written language gained strength.

It may be objected: the real father of Slavic philology should be called not Chernorizets Khrabra, but Cyril the Philosopher himself. But all the enormous philological knowledge of the Thessaloniki brothers (with the exception of the dispute with the Venetian trilinguals) is almost completely dissolved in their translation practice. And Brave in every sentence of “Answers” simply shines with the philological equipment of his arguments.

He writes both a treatise and an apology. Precise, even the most accurate for that era, information on the spelling and phonetics of comparable scripts and languages, supported by information from ancient grammars and commentaries on them, alternates under the pen of Brave with enthusiastic assessments of the spiritual and cultural feats of the brothers. This man's speech is in some places similar to a poem. The excited intonations of individual sentences vibrate like a song. In Brave’s speech, even if he goes into detail about the alphabetic structure of the alphabet, there is nothing of the ramblings of a bore scholastic.

Why is this literary monument called “Answers...”? The spiritual revolution carried out by Cyril and Methodius on the common field of two linguistic worlds, Slavic and Greek, one might guess, gave rise to a great many questions among the Slavs in the generation of the monk Brave. So he was about to answer the most persistent of truth seekers. Yes, the events are unprecedented. Their grandfathers are still alive, “simple children,” who had never even heard of Jesus Christ. And today in every church the clear parable of Christ about the sower, about the good shepherd, about the first and last at the feast sounds, and the call of the Son of Man resounds loudly to all who labor and are burdened... How did books suddenly begin to speak to the Slavs that were previously incomprehensible to them?.. Before, the Slavs did not have their own letters, and if anyone had them, then almost no one understood their meaning...

Yes, Brave agrees:

Previously, the Slavs did not have letters,

but they read by the features and cuts,

or they were guessing, being filthy.

Having been baptized,

Roman and Greek letters

tried to write Slavic speech without arrangement...

But not every Slavic sound, notes Khrabr, “can be written well in Greek letters.”

...And so it was for many years,

then God the lover of mankind, ruling over everything

and without leaving the human race without reason,

but bringing everyone to reason and to salvation,

had mercy on the human race,

sent them Saint Constantine the Philosopher,

named Kiril,

a righteous and true husband.

And he created thirty-eight letters for them -

some modeled on Greek letters,

others according to Slavic speech.”

“Following the example of Greek letters,” twenty-four signs were created, clarifies Chernorizets Khrabr. And, having listed them, a little lower he again emphasizes: “similar to Greek letters.” “And fourteen is in Slavic speech.” The insistence with which Brave speaks about the “pattern” and following it, about the sound correspondences and differences between the two letters, convinces: this cause-and-effect side of the matter is extremely important to him. Yes, Kirill the Philosopher took a lot into his alphabet almost for nothing. But he added a lot of important things for the first time, expanding the limited Greek alphabet series in the most daring way. And Brave will list every single letter of Kirill’s inventions that correspond specifically to Slavic articulatory abilities. After all, the Greek, we would add, simply does not know how to pronounce or pronounce very approximately a whole series of sounds that are widespread in the Slavic environment. However, the Slavs, as a rule, do not pronounce some sounds of Greek articulatory instrumentation very clearly (for example, the same “s”, which sounds with some hiss in the Greek). In a word, he gifted and limited everyone in his own way Creator of all kinds.

There is no need to accompany any line of Brave with explanations. His “Answers about Writings” are worthy of independent reading, and such an opportunity will be provided below, immediately after the main text of our story about two Slavic alphabets.

And here it is enough to emphasize: Khrabr honestly and convincingly reproduced the logic of the development of Slavic-Greek spiritual and cultural dialogue in the second half of the 9th century.

It is worthy of regret that some of the defenders of the “glagolic primacy” (especially the same F. Grevs, Doctor of Theology) tried to turn the arguments of the first Slavic philologist, clear as day, upside down. He, they are convinced, acts precisely as a brave supporter of... Glagolitic writing. Even when he talks about the Greek alphabet as an absolute model for Cyril. Because Brave supposedly does not mean the letters of the Greek graphics themselves, but only the sequence of the Greek alphabetical order. But even in the circle of verbatim scientists, there is a murmur about such overzealous manipulations.

Well, it is clear to the naked eye: in our days (as was the case in the 9th century), the question of the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet, as well as the question of the primacy of the Cyrillic or Latin alphabet in the lands of the Western Slavs, is not only philological, but, involuntarily, both confessional and political. The forced displacement of the Cyrillic script from the Western Slavic environment began in the age of the Thessaloniki brothers, on the very eve of the division of churches into Western and Eastern - Catholic and Orthodox.

The Cyrillic alphabet, as we all see and hear, is still subject to widespread force. It involves not only “eagles” - the organizers of a unipolar world, but also “lambs” - quiet missionaries of the West in the East, and with them “doves” - affectionate humanities-Slavists.

As if no one from this camp realizes that for us, who have lived for more than a thousand years in the expanding space of Cyrillic writing, our dear, beloved Cyrillic alphabet from the first pages of the primer is as sacred as the wall of the altar, like a miraculous icon. There are national and state symbols that it is customary to stand in front of - the Flag, the Coat of Arms, the Anthem. This includes our Letter.

The Slavic Cyrillic alphabet is evidence of the fact that since ancient times the Slavs of the East have been in spiritual kinship with the Byzantine world, with the rich heritage of Greek Christian culture.

Sometimes this connection, including the proximity of the Greek and Slavic languages, which has no analogues within Europe, nevertheless receives carefully verified confirmation from the outside. Bruce M. Metzger, in the work already cited, Early Translations of the New Testament, says: “The formal structures of Church Slavonic and Greek languages very close in all main features. Parts of speech, in general, are the same: verb (changes according to tenses and moods, person and number differ), names (noun and adjective, including participle, change according to numbers and cases), pronouns (personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative ; change by gender, case and number), numerals (inflected), prepositions, adverbs, various conjunctions and particles. Parallels are also found in the syntax, and even the rules for constructing words are very similar. These languages are so close that in many cases a literal translation would be quite natural. There are examples of excessive literalism in each manuscript, but on the whole it seems that the translators had a perfect knowledge of both languages and tried to reproduce the spirit and meaning of the Greek text, deviating as little as possible from the original.

“These languages are so close...” For all his academic dispassion, Metzger's assessment of the unique structural similarities of the two linguistic cultures comes at a price. In the entire study, a characteristic of this kind was heard only once. Because the scientist, having examined other old languages of Europe, did not find any basis to say about the same degree of closeness that he noted between Greek and Slavic.

But it’s time to finally return to the essence of the issue about the two Slavic alphabet. As far as a comparison of the oldest written sources of the Church Slavonic language allows, the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet coexisted quite peacefully, although forcedly, competitively, during the years of missionary work of the Thessalonica brothers in Great Moravia. They coexisted - let's say a modernist comparison - just as two design bureaus with their own original projects compete within the same goal setting. The initial alphabetical plan of the Thessaloniki brothers arose and was realized even before their arrival in the Moravian land. He declared himself in the guise of the first Cyrillic alphabet, compiled with abundant use of the graphics of the Greek alphabet and the addition of a large number of letter correspondences to purely Slavic sounds. The Glagolitic alphabet in relation to this alphabetic structure is an external event. But one that the brothers had to reckon with while in Moravia. Being an alphabet that was defiantly different in appearance from the most authoritative Greek letter in the Christian world at that time, the Glagolitic alphabet quickly began to lose its position. But her appearance was not in vain. The experience of communicating with her letters allowed the brothers and their students to improve their original letter, gradually giving it the appearance of the classical Cyrillic alphabet. It was not for nothing that the philologist Chernorizets Khrabr remarked: “It’s easier to finish something later than to do the first thing.”

And here is what, many centuries later, the strict, picky and incorruptible writer Leo Tolstoy said about this brainchild of Cyril and Methodius: “The Russian language and the Cyrillic alphabet have a huge advantage and difference over all European languages and alphabets... The advantage of the Russian alphabet is that every the sound is pronounced in it - and it is pronounced as it is, which is not in any language.”

2.4.5. Comparative table of Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets

Key words: paleoslavic studies, Revnerussian language, Slavic alphabet, Glagolitic alphabet, Cyrillic alphabet, sources of Glagolitic alphabet, sources of Cyrillic alphabet, Slavic letters, alphabet correlation

Name of letters

All letters, like Greek ones, had a name, but these names were not blindly transferred from Greek, they were actually Slavic.

V. Georgiev believed that the names of letters in the alphabet are remnants that have not reached us. Its author (perhaps it was K. Ohridski) took the first words of the prayer and compiled them into a chain of words that made it easier for his students to learn the Slavic alphabet. It is also assumed that these words, arranged in a certain sequence, had the meaning of the text. But their forms changed when rewritten, and the meaning of the chain of words was lost.

| Letter names | Possible reconstruction of the text |

|---|---|

|

Number of letters

The Cyrillic alphabet has 43 letters, and the Glagolitic alphabet has 40 letters. There were no letters in the Glagolitic alphabet, but there was a letter.

It is assumed that the original Slavic alphabet - Glagolitic - was used in the 9th - early 10th centuries. a different composition, it had 38 characters, as evidenced by the Monk Khrabr (for comparison: the Greek alphabet, which formed the basis of the Slavic writing system, consisted of only 24 letters). Probably it was not and, perhaps, was perceived not as a special letter, but as a combination of two letters. Proof of this is the fact that iotated vowels are not found in the oldest manuscripts.

Thus, initially there were 38 letters in the Cyrillic alphabet, and 38 in the Glagolitic alphabet (39, if you count).

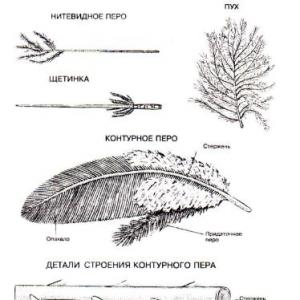

Letter outlines

The shape of the letters of the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet, which had different sources, was fundamentally different.

- In the Cyrillic alphabet, the shape of the letters was simple, geometrically clear and easy to write;

- The shape of the Glagolitic letters was extremely complex and intricate, with many loops and curls.

In connection with the graphic proximity of the Cyrillic alphabet to the Byzantine alphabet, and the Glagolitic alphabet to the Greek alphabet, the question of the degree of independence of the Slavic alphabet acquires special significance

Numerical value of letters

Like the letters of the Greek alphabet, the letters of the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet had, in addition to sound, also a numerical value.

In the Cyrillic alphabet, only letters borrowed from the Greek alphabet had a numerical value, and these 24 letters were assigned the same numerical value that they had in the Greek numerical system. The exceptions are the following cyrillic letters, for which the Greek letter used letters that had long lost their sound meaning (therefore, in the Cyrillic alphabet, newly acquired letters were used for this):

If a letter was used to indicate a number, a title was placed above it, and dots were placed on the sides:

In the Glagolitic alphabet, each letter without gaps from to had its own numerical value.

Here's a little more detail on the topic:

On May 24, Russia and a number of other countries celebrated the Day of Slavic Literature and Culture. Remembering the enlightenment brothers Cyril and Methodius, people often stated that it is thanks to them that we have the Cyrillic alphabet.

As a typical example, here is a quote from a newspaper article:

Equal to the Apostles Cyril and Methodius brought to Slavic land writing and created the first Slavic alphabet (Cyrillic alphabet), which we use to this day.

By the way, on icons of Saints Cyril and Methodius they are always depicted with scrolls in their hands. On the scrolls are the well-known Cyrillic letters - az, beeches, vedi...

Here we are dealing with a long-standing and widespread misconception, says senior researcher at the Institute of Russian Language named after V.V. Vinogradova Irina Levontina: “Indeed, everyone knows that we owe our letter to Cyril and Methodius. However, as often happens, everything is not quite like that. Cyril and Methodius are wonderful monastic brothers. It is often written that they translated liturgical books from Greek into Church Slavonic. This is incorrect because there was nothing to translate into, they created this language. Sometimes they say that they translated into South Slavic dialects. That's funny. Try to come to some village where there is such a completely unwritten dialect, no television, and translate not even the Gospel, but a physics or history textbook into this dialect - nothing will work. They practically created this language. And what we call the Cyrillic alphabet was not invented by Kirill. Kirill came up with another alphabet, which was called “Glagolitic”. It was very interesting, unlike anything else: it consisted of circles, triangles, and crosses. Later, the Glagolitic alphabet was replaced by another letter: what we now call the Cyrillic alphabet - it was created on the basis of the Greek alphabet.”

“The debate about which alphabet is primary, Cyrillic or Glagolitic, is almost 200 years old. Currently, the opinions of historians boil down to the fact that the Glagolitic alphabet is primary, it was St. Cyril who created it. But there are many opponents to this point of view.” There are four main hypotheses about the origin of these Slavic alphabets.

The first hypothesis says that the Glagolitic alphabet is older than the Cyrillic alphabet, and arose even before Cyril and Methodius. “This is the oldest Slavic alphabet, it is unknown when and by whom it was created. The Cyrillic alphabet, familiar to us all, was created by Saint Cyril, then still Constantine the Philosopher, only in 863,” he said. - The second hypothesis states that the oldest is the Cyrillic alphabet. It arose long before the start of the educational mission among the Slavs, as a letter developing historically on the basis of the Greek alphabet, and in 863 Saint Cyril created the Glagolitic alphabet. The third hypothesis suggests that the Glagolitic alphabet is a secret script. Before the start of the Slavic mission, the Slavs did not have any alphabet, at least a working one. In 863, Cyril, then still Constantine, nicknamed the Philosopher, created the future Cyrillic alphabet in Constantinople, and went with his brother to preach the Gospel in the Slavic country of Moravia. Then, after the death of the brothers, during the era of persecution of Slavic culture, worship and writing in Moravia, from the 90s of the 9th century, under Pope Stephen V, the followers of Cyril and Methodius were forced to go underground, and for this purpose they came up with the Glagolitic alphabet, as encrypted reproduction of Cyrillic alphabet. And finally, the fourth hypothesis expresses the idea directly opposite to the third hypothesis that in 863 Cyril in Constantinople created the Glagolitic alphabet, and then, during the era of persecution, when the Slavic followers of the brothers were forced to flee from Moravia and move to Bulgaria, it is not known exactly by whom, Perhaps their students created the Cyrillic alphabet, based on the more complex Glagolitic alphabet. That is, the Glagolitic alphabet was simplified and adapted to the familiar graphics of the Greek alphabet.”

According to Vladimir Mikhailovich, the widespread use of the Cyrillic alphabet has the simplest explanation. The countries in which the Cyrillic alphabet was established were in the sphere of influence of Byzantium. And she used the Greek alphabet, with which the Cyrillic alphabet is seventy percent similar. All letters of the Greek alphabet are included in the Cyrillic alphabet. However, the Glagolitic alphabet did not disappear. “It remained in use literally until the Second World War,” said Vladimir Mikhailovich. - Before the Second World War, Croatian newspapers were published in Glagolitic in Italy, where Croats lived. The Dolmatian Croats were the guardians of the Glagolitic tradition, apparently striving for cultural and national revival.”

The basis for the Glagolitic script is the subject of much scientific debate. “The origins of his writing are seen in Syriac script and Greek cursive. There are a lot of versions, but they are all hypothetical, since there is no exact analogue, says Vladimir Mikhailovich. - “It is still obvious that the Glagolitic font is of artificial origin. This is evidenced by the order of letters in the alphabet. The letters stood for numbers. In the Glagolitic alphabet everything is strictly systematic: the first nine letters meant units, the next - tens, the next - hundreds.

So who invented the Glagolitic alphabet? That part of the scientists who talk about its primacy believe that it was invented by St. Cyril, a learned man, librarian at the Church of St. Sophia in Constantinople, and the Cyrillic alphabet was created later, and with its help, after the blessed death of St. Cyril, the work of enlightening the Slavic peoples continued by Cyril’s brother Methodius, who became Bishop of Moravia.

It is also interesting to compare the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet by letter style. In both the first and second cases, the symbolism is very reminiscent of Greek, but the Glagolitic alphabet still has features characteristic only of the Slavic alphabet. Take, for example, the letter “az”. In the Glagolitic alphabet it resembles a cross, and in the Cyrillic alphabet it completely borrows the Greek letter. But this is not the most interesting thing in the Old Slavonic alphabet. After all, it is in the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet that each letter represents a separate word, filled with the deep philosophical meaning that our ancestors put into it.

Although today letter-words have disappeared from our everyday life, they still continue to live in Russian proverbs and sayings. For example, the expression “start from the beginning” means nothing more than “start from the very beginning.” Although in fact the letter “az” means “I”.

From the period of activity of Constantine the Philosopher, his brother Methodius and their closest disciples, i.e. from the second half of the ninth century, unfortunately, no written monuments have reached us, except for the relatively recently discovered inscriptions on the ruins of the church of King Simeon in Preslav (Bulgaria).

These inscriptions by some scientists (for example, E. Georgiev) refer to recent years IX century; other scientists dispute this dating and attribute the Preslav inscriptions to the 10th-11th centuries. By the 10th century include all the other ancient Slavic inscriptions that have come down to us, as well as the most ancient manuscripts.

And so, it turns out that these ancient inscriptions and manuscripts were made not with one, but with two graphic varieties of Old Church Slavonic writing. One of them received the conventional name “Cyrillic” (from the name Kirill, adopted by Constantine the Philosopher when he was tonsured a monk); the other received the name “glagolitic” (from the Old Slavonic “verb”, which means “word”).

The presence of such two graphic varieties of Slavic writing still causes great controversy among scientists. After all, according to the unanimous testimony of all chronicles and documentary sources, Constantine the Philosopher, before leaving for Moravia, developed one Slavic alphabet. Where, how and when did the second alphabet appear? And which of the two alphabets - Cyrillic or Glagolitic - was created by Constantine?

These questions are closely related to others, perhaps even more important. Didn’t the Slavs have some kind of written language before the introduction of the alphabet developed by Constantine? And if such writing existed, what was it, how did it arise, and what social needs did it serve?

Before moving on to consider these complex issues that have not yet been fully resolved by science, you need to get acquainted with the ancient Slavic alphabets - Cyrillic and Glagolitic. In their alphabetic composition, the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets were almost identical.

The Cyrillic alphabet, according to the 11th century manuscripts that have reached us, had 43 letters.

Glagolitic, according to monuments from approximately the same time, had 40 letters. Of the 40 Glagolitic letters, 39 served to convey almost the same sounds as the letters of the Cyrillic alphabet, and one Glagolitic letter - “derr”, which was absent in the Cyrillic alphabet, was intended to convey the palatal (soft) consonant g; in the oldest Glagolitic monuments of the 10th-11th centuries that have come down to us, “derr” usually served to convey the sound g, standing before the vowels e, and (for example, in the word “angel”)2. There were no letters in the Glagolitic alphabet similar to Kirill’s “psi”, “xi”, as well as iotized letters e, a.

This was the alphabetical composition of the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet in the 11th century. In the IX-X centuries. their composition was apparently somewhat different.

Thus, in the initial composition of the Cyrillic alphabet, apparently, there were not yet four iotized letters (two iotized “yus”, as well as iotated a, e). This is confirmed by the fact that in the oldest Bulgarian Cyrillic manuscripts and inscriptions all four indicated letters are missing (the inscription of Tsar Samuil, “Leaves of Widolsky”) or some of them (“Savvina’s book”, “Suprasl manuscript”). In addition, the letter “uk” (ou) was probably initially perceived not as a special letter, but as a combination of “on” and “izhitsy”. Thus, the initial Cyrillic alphabet had not 43, but 38 letters.

Accordingly, in the initial composition of the Glagolitic alphabet, apparently, there were not two, but only one “small yus” (the one that later received the meaning and name of “iotated small yus”), which served to designate both the iotized and uniotated nasal vowel sound e . The second “small yus” (which later received the meaning and name of “uniotated small yus”) was apparently absent in the original Glagolitic; this is confirmed by the graphics of the oldest Glagolitic manuscript - the “Kyiv Leaves”. Perhaps one of the two “big yus” (which later received the meaning and name “iotated big yus”) was also missing from the initial Glagolitic; in any case, the origin of the form of this Glagolitic letter is very unclear and is probably explained by imitation of the late Cyrillic alphabet. Thus, the initial Glagolitic alphabet had not 40, but 38-39 letters.

Like the letters of the Greek alphabet, Glagolitic and Cyrillic letters had, in addition to sound, also a digital meaning, that is, they were used to designate not only speech sounds, but also numbers.

At the same time, nine letters served to designate units (from 1 to 9), nine - for tens (from 10 to 90) and nine - for hundreds (from 100 to 900). In Glagolitic, in addition, one of the letters denoted a thousand; in Cyrillic, a special sign was used to designate thousands. In order to indicate that the letter denotes a number and not a sound, the letter is usually highlighted on both sides with dots and a special horizontal line is placed above it - “title”.

In the Cyrillic alphabet, as a rule, only letters borrowed from the Greek alphabet had digital values: each of 24 such letters was assigned the same digital value that this letter had in the Greek digital system.

The only exceptions were the numbers 6, 90 and 900. In the Greek digital system, the letters “digamma”, “coppa”, “sampi” were used to transmit these numbers, which had long ago lost their sound meaning in Greek writing and were used only as numbers. These Greek letters were not included in the Cyrillic alphabet. Therefore, to convey the number 6 in Cyrillic, the new Slavic letter “zelo” was used (instead of the Greek “digamma”), for 90 - “worm” (along with the sometimes used “kopnaya”) and for 900 - “tsy” (instead of “sampi” ).

Unlike the Cyrillic alphabet, in the Glagolitic alphabet the first 28 letters in a row received a numerical value, regardless of whether these letters corresponded to Greek or served to convey special sounds of Slavic speech. Therefore, the numerical value of most Glagolitic letters was different from both Greek and Cyrillic letters.

The names of the letters in the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet were exactly the same; however, the time of origin of these names (especially in the Glagolitic alphabet) is unclear.

The order of letters in the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets was almost the same. This order is established, firstly, based on the numerical value of the letters of the Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabet, and secondly, on the basis of the alphabetic acrostics that have come down to us (a poem, each line of which begins with the corresponding letter of the alphabet in alphabetical order) of the 12th-13th centuries, in third, based on the order of letters in the Greek alphabet.

Cyrillic and Glagolitic differed greatly in the shape of their letters. In the Cyrillic alphabet, the shape of the letters was geometrically simple, clear and easy to write. Of the 43 letters of the Cyrillic alphabet, 24 were borrowed from the Byzantine charter, and the remaining 19 were constructed more or less independently, but in compliance with the uniform style of the Cyrillic alphabet.

The shape of the Glagolitic letters, on the contrary, was extremely complex and intricate, with many curls, loops, etc. But the Glagolitic letters were graphically more original than the Kirillov ones, and were much less like the Greek ones.

Despite the seemingly very significant difference, many letters of the Glagolitic alphabet, if freed from curls and loops, are close in shape to similar letters of the Cyrillic alphabet. The similarity of Glagolitic letters is especially great with those Cyrillic letters that were not borrowed from the Greek charter, but were created to convey special sounds of Slavic speech (for example, the letters “live”, “tsy”, “worm”, “shta”, etc.); one of these letters (“sha”) in the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet is even exactly the same. The attention of researchers was also attracted by the fact that the letters “shta”, “uk” and “era” in the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet were ligatures from other letters. All this indicated that one of the alphabet once had a strong influence on the other.